by Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman

It seems that we have gone from the winter to summer flying season in a very short time though winter did its best to hang on much longer than usual in the Midwest. As pilots came out of winter hibernation, I became extremely busy flying and missed the deadline for my column in the last issue for which I apologize to my readers. I would like to congratulate Andy Nahas of Boscobel, Wis., Jack Young of Madison, Wis., and Peter Kendler of Lincolnshire, Ill. on obtaining their instrument ratings and Ben Fischer of Spring Grove, Ill. on the purchase and delivery of his new G36 Bonanza. I was honored to have had the opportunity to instruct and fly with these fine pilots.

As continued interest has been focusing on ADSB, I will be focusing a brief part of this column on the Garmin GPS 796 and the companion GDL 39 ADSB receiver. Even though the icing threat for most general aviation pilots is behind us for a while, I would like to touch on that subject at the request of several of our readers. A question on approach plates is another topic I would like to address and I must say that this one still requires quite a bit of research.

Whenever there is a general aviation accident involving a high-profile person, it makes national news as in the case of Richard Rockefeller. I would like to add a few comments of my own about the situation surrounding this accident.

There have been many writers making comparisons of the different ADSB devices, and I will add some of my own comments as well (fig 1). I had the chance to fly the Garmin GPS 796 mated to the Garmin GDL 39 and make some of my own observations.

Many have compared the GPS 796 with the iPad, and I will have to do the same. We have definitely made progress in the release of new GPS/ADSB units, and the competition is very keen. I felt the size of the Garmin 796 seemed better for the cockpit environment compared to a full size iPad that must be kept on your knee, or if mounted, covers up some important aircraft switches or indicators.

We used the Garmin 796 with the GDL 39 that has ADSB weather and traffic, but the 796 can also use XM weather. For the most part, I prefer the XM weather over ADSB weather because of its availability on the ground and more available weather products. The cost of the subscription needs to offset this advantage and with pilots flying fewer hours per year, this may be hard to justify.

The traffic on the Garmin package is not giving you the full traffic display because all aircraft are not yet ADSB out equipped and Garmin displays this warning. Approach plates are displayed on the 796 with a subscription, but this is quite expensive – $499.00 compared to the iPad apps costing $99. I have both Wing X Pro and Foreflight on my iPad, which allows me to test different manufacturers’ interface boxes and that amounts to around $200.00 per year. The Garmin 796 does a good job at what it was designed to do and may be worth its price times 10 if your iPad should fail at the wrong time due to overheating as mine has done several times in the cockpit. The Garmin 796 GDL 39 combo has never done that, so you decide.

The legal interpretation of flight into icing conditions in aircraft not equipped for known ice has plagued many pilots flying in the winter.

What legal action might the FAA take should you get into more ice than you can handle and declare an emergency? I asked a FSDO inspector friend of mine for an interpretation of the rule, and he gave me the official answer as defined in a letter addressed to Ms. Leisha Bell, Manager of Regulatory Affairs with AOPA, from the FAA Office of Chief Council.

I would like to point out several items addressed from that letter: The first referencing the aircraft owners manual stating, “This aircraft is not approved for flight into known icing conditions.” FAA regulation 14CFR 91.9 (a) references the approved aircraft flight manual as compliance with these requirements by the pilot. The letter elaborates the fact that this is known icing conditions and the pilot needs to be aware of this.

Specifically, I quote the letter as to conditions for known icing to occur: “The formation of structural ice requires two elements 1) The presence of visible moisture, and 2) An aircraft surface temperature at or below zero degrees Celsius.” These are factors that I totally agree with, and “YES,” you will get ice. The question is how much? You may get a few thousands of an inch in one hour’s flight time in these conditions, or you may get an inch or more in a minute or less.

On May 1, 2014, I was flying with an instrument student pilot to Ohio State University Airport (KOSU) in Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC) at 5,000 ft. The temperature was around zero degrees Celsius, give or take a degree for the entire trip, with no noticeable ice accumulation. Around the Peotone VOR (EON) we hit a pocket of moisture and accumulated 3/8 inch of mixed ice in about a minute. We were not in trouble, as we knew warmer temperatures were below us as METARS and pilot reports showed good VFR under us. We continued at 5,000 ft. for about 5 minutes and lost about 25 kts of airspeed due to the shape of the mixed ice. After requesting a lower altitude from ATC, we descended to 4,000 ft. and the ice melted off.

I wish I could nail down a better definition on the icing rule, but it just is not there. Before Nexrad in the cockpit, I would not fly with forecast imbedded thunderstorms because we did not know where they were. It would be nice to know where those pockets of ice were, so we could avoid them as well. Unfortunately, we do not have the technology yet. Pilot reports are still our best answer to where the ice is, and we made such a report on our encounter. Keep the ice for those cold drinks.

On a recent visit to Marshfield, Wis. on a training flight, I had the opportunity to see a flying friend from my past of about 50 years, Dan Maurer. Dan is retired and had a great flying career beginning with Midstate Airlines, and then with Northwest Airlines, recently retiring with Delta Airlines.

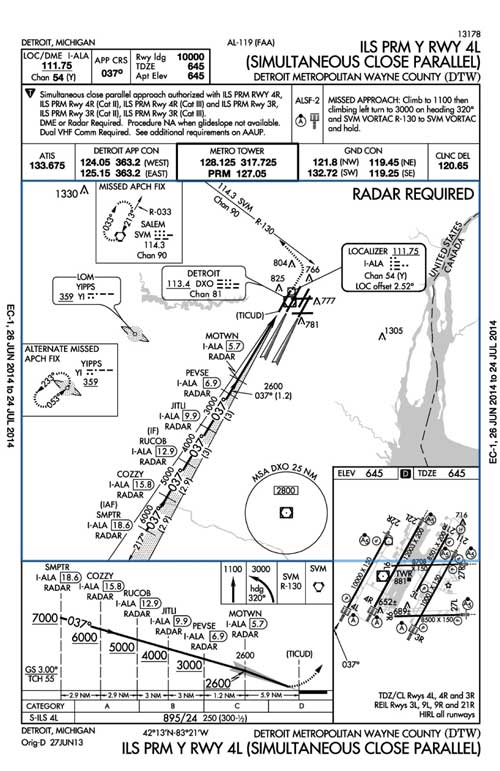

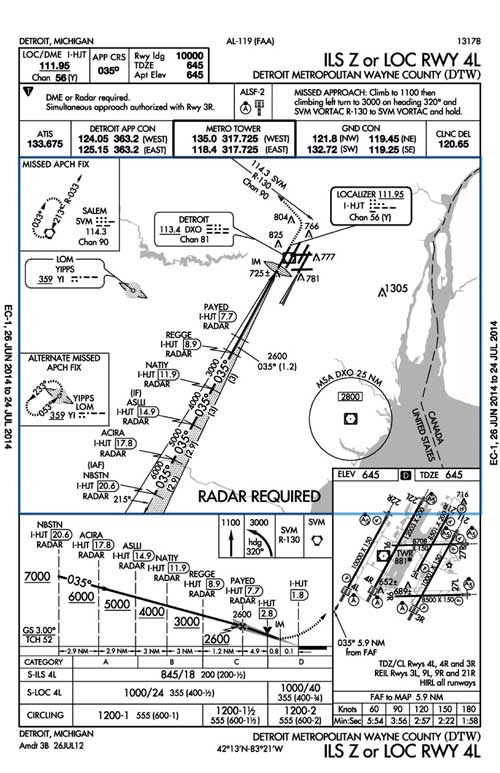

We always find something interesting in aviation to talk about, and Dan posed a question to me on approach plates. The question was on approach plates with the designation of Y and Z in the approach name. I proceeded to explain how the GPS Y and Z differed and Dan said, “ WHOA; but, these are ILS approaches”(fig 2 & fig 3). I did not have an answer, so I left Dan thinking, “what are these naughty *TERPSters doing now.” So the challenge begins!

Items I have been able to determine from the RNAV (GPS), Y and Z approaches do not seem to follow through to the new challenge when applied to the ILS Y and Z approaches. To begin, most of us are familiar with the circling approaches A and B and down the line. The “A” approach is the first circling approach to the airport and if a second circling approach is available, it is labeled B then C and down the line. The reverse is true for the Y and Z approaches with Z being the first approach for a specific runway and going backward through the alphabet. On the RNAV (GPS) Y and Z approaches, the waypoint string and altitudes are the same except the final Decision Altitudes (DA) or Minimum Descent Altitudes (MDA), do not seem to follow through on the ILS Y and Z approaches. A second note is that on some of the RNAV Y approaches, they do not list GPS in the title of the approach, meaning they are designed for RNAV systems, which use different criteria for determining protected airspace for the approach corridor. A third criteria applying to the RNAV Y approach is that some are labeled “SAAAR,” meaning Special Aircrew & Aircraft Authorization Required. FAA AC90-101 further describes and provides information on obtaining this approval.

The *TERPSters and Dan have brought me to my knees on this one; but having a quest for knowledge, I will continue to research and investigate more on the Y & Z approaches and share it with our readers in future issues of Midwest Flyer Magazine.

Whenever a high profile person is involved in a general aviation accident, it becomes the attention of the news media, as did the recent tragic accident involving Richard Rockefeller. My sympathy and condolences go out to the family and friends of Richard.

By the preliminary investigation of the accident by the FAA, one item gets our attention and that is the low weather conditions surrounding the accident. The media also brings out the fact that Richard was not a low-time, inexperienced pilot.

A number of years ago, I set forth a goal to determine measurable criteria and set a minimum weather safety standard for flying in our Beechcraft training program. Some of these thoughts went into setting our standard and may or may not apply to the tragic Rockefeller accident:

1) For Bonanza and Baron aircraft, do they have single or dual control yoke, and is the pilot and instructor both current for flight into IMC?

2) Are there any known equipment problems or deficiencies?

3) Are thunderstorms forecast or imminent?

4) What is the current ceiling and visibility?

To cover these questions with a brief answer:

1) Both pilot and instructor need to be current for single control yoke for takeoff into IMC.

2) No known equipment problems.

3) Two forms of thunderstorm avoidance in the airplane (Nexrad WX, Stormscope, live airborne radar).

4) A ceiling or visibility equal to or better than the lowest published circling approach minimums for the departure airport.

None of us should attempt to be a Monday morning quarterback on the crash of Richard Rockefeller, but items mentioned above might be used as a guide to prevent another sad incident. On pilot checkrides, the examiner now has some special emphasis items from the FAA to help a pilot determine if they are safe for flight. I will cover more of my thoughts on these in the next issue of Midwest Flyer Magazine.

Fly safe and avoid those summertime thunderstorms!

*TERPSters “The people that design and write the Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS).

EDITOR’S NOTE: Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman is a Certified Instrument Flight Instructor (CFII) and the program manager of flight operations with “Bonanza/Baron Pilot Training,” operating out of Lone Rock (LNR) and Eagle River (EGV), Wisconsin. Kaufman was named “FAA’s Safety Team Representative of the Year for Wisconsin” in 2008. Email questions to captmick@me.com or call 817-988-0174.