by Jim Hanson

I recently had the opportunity to do something REALLY different–and REALLY fun in aviation! A national association of pilots (the name cannot be revealed because by their codebook; they seek no publicity) is made up of “aviators of note.” Suffice to say that these aviators are “people who know people.” These people have been able to provide me access to many experiences that most people would find impossible, and to otherwise off-limits places.

Like most people growing up in the 1950s and ’60s, we followed the progress of the “Space Race.” Since I flew corporate jets, I was especially interested in the Space Shuttle–a rocket that returned from orbit to land like an airplane. In 1981, I had moved to Houston from Minnesota. While in Minnesota, I taught a friend how to fly balloons and seaplanes, and he taught me to fly helicopters. After moving to Houston, he suggested I look up his brother, who was in charge of the Reality Systems Integration Division of NASA for the Space Shuttle.

Reality Systems Integration developed a simulator to teach astronauts what they THOUGHT the unpowered shuttle Enterprise would fly like when released from the Boeing 747 carrier aircraft to glide to a landing at Edwards Air Force Base. When the flight was successfully made, they took the telemetry data from those flights to correct the simulator for what the Shuttle REALLY flew like (thus, Reality Systems Integration). When Columbia made the first orbital flight, they again took real-time information to correct and perfect the simulator. Only two weeks after that first flight, I was invited to fly the simulator. I flew the actual Shuttle simulator in orbit and did two landings. It was an unforgettable experience! (See sidebar)

The local chapter of that national pilot group, located at Vero Beach, Florida, is located very close to the Kennedy Space Center (Cape Canaveral, for those of us of a certain age). This group knows people, and when I saw in the organization’s national magazine that they were putting together a chance to actually land at the restricted Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF), I jumped at the chance. This would be “closure” for me, starting out when the Shuttle was new, landing at Edwards in the sim, and now landing at the Shuttle facility at the Cape 35 years later, after all of the Shuttles had been retired. My brother, Bob, had joined me on that earlier Houston experience; he would join me for this last chapter of the Shuttle experience.

I had been to the Cape several times before to visit the historic launch sites and to see what was going on today. I immediately committed to fly to the Cape to land on the Shuttle runway, but I put in a request with the local pilot’s group asking if they could they assist me in arranging a simulated Shuttle approach and landing on the famed runway. They agreed to help. They put me in contact with Jimmy Moffitt, Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) manager.

Moffitt explained that since the strip is no longer required for Shuttle use, it is leased to Space Florida–a private firm that operates the facility. The SLF is still government property and is on a government facility, but Space Florida is a private firm that is developing business use for the facility, as NASA is now partnering with industry to develop commercial spacecraft. I explained that I would like to replicate the glidepath and deadstick landing of the Space Shuttle. We immediately found common ground in discussing the problems in doing so.

The Shuttle had an “over-the-fence” speed of about 215 knots (depending on weight) on landing. It has a glide ratio of only about 3.7 to 1 at subsonic speeds (or, as I describe it, “Like a loaded Tri-Pacer on a hot day”–about the same “glide” as a helicopter in autorotation). This would require a glideslope approximately seven (7) times steeper than a normal airline approach, and at Shuttle landing speeds, about 6,000 feet per minute in the descent, or 100 feet per second. Most piston airplanes can’t descend that fast, and most jets can’t get down that fast, either. (NASA modified Gulfstream II jets as Shuttle trainers by leaving the nose gear retracted while extending the main gear, installing “reflex” drag flaps, and taking the unusual step of allowing the engines to be reversed in flight in order to meet the mission profile of a returning Shuttle).

From experience with the King Air 200 that I fly, I knew that I could match that rate of descent with gear and approach flaps out, and props in flat pitch without hurting the engines. An added benefit was that since the King Air uses PT-6 free turbines, the little jet power section would continue to run if the props were feathered–an important safety feature.

To actually touch down at the SLF, you have to have prior permission. You must submit the landing request form, and you must name NASA, Space Florida, and everyone else as a named insured on your insurance policy. These are only minor inconveniences… WE WERE GOING TO LAND AT THE CAPE, NO MATTER WHAT!

Moffitt put me in touch with the SLF tower, and we briefed my request. There would be 20 other aircraft also landing on the strip, but ours would be the only Shuttle approaches. I filed for the Shuttle Landing Facility (identifier KTTS) on January 29, 2016. Our estimated time enroute for the 1090 nm flight was 3 hours 41 minutes, so we departed at 9:30 a.m. CST to arrive at our landing “window” at the Cape. Along our route, controllers asked, “Are you really landing at the SLF, or going to Titusville?” I assured them that we were indeed going to the Cape.

The first problem occurred when Orlando Approach wouldn’t give us the 10,000 ft. initial altitude for a landing at the Cape. Even though I cancelled IFR, they took us down to 5500 feet. When I contacted the SLF tower, they recognized our landing authority, and I told them we wanted to do a Shuttle Profile. They were unable due to four inbound aircraft, some of which were still on an IFR flight plan. I told them that we had plenty of fuel, and would hold. We could have done a 360-degree Jet Penetration, and over-fly the runway, then break onto a curved downwind/base/final approach. It would have been far easier to “play” the approach. If we found ourselves a little low, we could have simply cut the inside of the turn radius. HOWEVER, the Shuttles didn’t make the overhead approaches (unless landing at Edwards AFB), so neither would we. I waited until all traffic was clear, then was cleared for the approach.

Though the Shuttles had five redundant onboard computers to compute glide path and energy state, we had none. I had done calculations for several “key positions” during the approach–distance from the threshold vs. altitude–but they were all for naught as our initial altitude didn’t match any of them. We would be shooting this approach using the TLAR method (That Looks About Right).

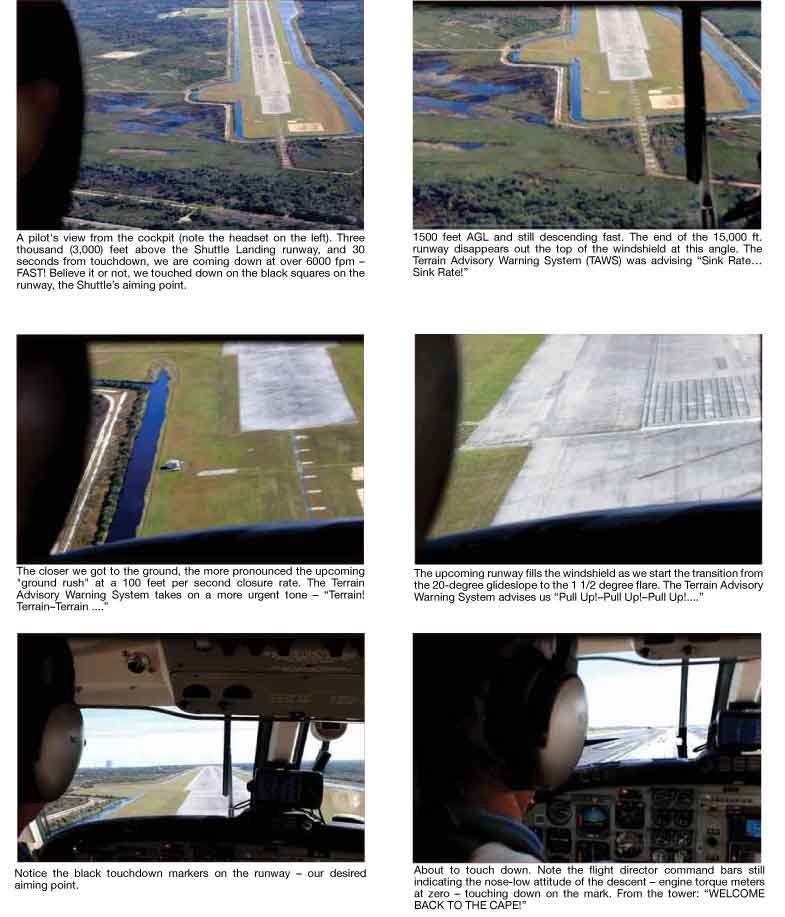

“HERE WE GO!” I told my brother, as I extended gear and flaps and closed the throttles, silencing the gear warning horns in the process. Though I was used to steep approaches in the King Air (pilots new to turboprops aren’t used to the tremendous amount of drag in a “full dirty” configuration), spot landings in this configuration are not normal. The touchdown aim point was a black mark on the runway, about 2,500 feet down the 15,000 ft. runway. (Shuttle pilots do NOT want to be short!)

The Ground Proximity Warning System was shouting “Sink Rate! Sink Rate!” in my ear, quickly changing to “Terrain!, Terrain!, Terrain!” warnings, then to an even more urgent “Pull UP!, Pull UP!, Pull UP!” as we neared the ground. We touched down right on the black target. I had no time to ask if brother Bob, my cameraman, had captured the landing from his position behind and between the pilot seats. Even though we had briefed the procedure, he was alarmed at the steep approach, and actually had bruises on his arm from steadying himself against the cockpit doorway while filming. He initially was not able to film the runway due to it being out of sight on the top of the cockpit windshield, but was able to get low enough to find and center the shot.

I had asked the tower for the “option” (stop and go, touch and go, or full stop landing) and now asked for another approach. We were cleared to a right downwind and the initial point 6.5 miles north of the runway. I asked tower if they could coordinate with Orlando Approach for a 10,000 ft. altitude… “Negative; we have traffic in the area,” but they did give us 7,500 feet for this approach. Again, there was traffic in the area when we switched to tower, but they eventually cleared us for a visual approach, and asked if we had the Baron traffic on a 2-mile final. We did, but said we would hold off on the approach, as we would quickly overtake him on a high-speed approach. This time, I elected to go with flaps approach and gear at the 182 knot limiting speed. Our true airspeed at altitude was 200 knots in this configuration, but the tailwind component gave us the same 215 knots as the Shuttle experienced on final approach. At this high speed, the rate of descent would have to be even steeper than the last approach, and we wouldn’t have the drag of full flaps. I countered this by pushing the props full forward for additional drag. We were cleared for the approach, and again, used a “TLAR” method of when to pull the power. With the steep approach, the runway filled the windshield (the approach is SO steep that Shuttles wouldn’t land in winds over 35 mph, as they couldn’t see the entire runway). We again put it on the mark, and told tower that this would be full stop.

Upon landing, we taxied the remaining 2 miles to the turnoff. Once parked, we were met by Jimmy Moffitt – the person who helped make it all possible!

Our intentions was to have the aircraft stay overnight at the SLF, but since there is no fuel available, the organizers had us relocate to Titusville (KTIX), only 8 miles away. We secured the aircraft and boarded shuttle busses provided by our hosts to go to our hotel. Our hosts at Vero Beach had a busy weekend planned for us! At dinner Friday evening, we met our Vero Beach hosts in person. We were introduced to Apollo 15 astronaut Al Worden (flew the lunar orbiter) and six-time Shuttle pilot Jon McBride. They not only related NASA stories about their missions, but answered unceasing questions for two days. Bob Cabana –Cape Administrator – also addressed us. While many have lamented the wind-down of the Lunar and Shuttle programs, Cabana stressed that NASA was as busy as ever, partnering with industry on new projects.

On Saturday, we had a full day ahead, touring the Space Center, initially on foot. We then adjourned for lunch at a dining room marked “crew only”–a true insider’s view–where we were again addressed by NASA heads. We were entertained with NASA films, and even a simulated Shuttle ride, all the while being ushered along through back entrances. We boarded busses to tour the compound, as our astronauts not only provided narration, but answered unending questions. We finished the day visiting the NASA space flight museum, where we viewed the magnificent lunar rocket, the Saturn V, then adjourned for a private catered dinner under the Space Shuttle Atlantis on display in its new building. What a MACHINE! What PEOPLE! And what an EDUCATIONAL WEEKEND!

This was a trip for the record books, all made possible by people who share our passion for flight. You won’t be able to do ALL of the things we did, but you can do MANY of them. It’s a wonderful vacation destination, and you, your friends, and your kids/grandkids will be inspired. Consider taking a trip to the Cape for an adventure on your own.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Jim Hanson is the long-time manager of the Albert Lea, Minnesota airport. Even before this flight, people often described him as “spacy.” If you would like to bring Jim “down to Earth,” he can be reached at his airport office at 507-373-0608, or jimhanson@deskmedia.com