by Russell A. Klingaman

In my legal career, I have been asked to help several pilots who have had their flying privileges put in jeopardy due to the consumption of alcohol. Usually, these cases involve circumstances unrelated to any flying activities. This article discusses the FAA approach to the consumption of alcohol by pilots.

In the United States, beverages containing alcohol are widely advertised, inexpensive, and readily available. They are often sold at liquor stores, gas stations, grocery stores, and similar retail establishments. Drinking alcohol is widely accepted in the U.S. Beverages containing alcohol are frequently served at meals, social gatherings, sporting events, and celebrations. In fact, many adolescents perceive drinking alcohol – and getting drunk – as a right of passage into adulthood.

Millions of people in this country – including many pilots – consume alcohol-containing beverages on a regular basis without jeopardizing their health, careers, friendships, or family relationships. On the other hand, there are millions of other people who use alcohol in ways, which are detrimental to their own health and/or the health of other people. Some people in this second group may be pilots.

FAA Alcohol-Related Regulations

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has enacted several rules governing the use of alcohol by pilots including:

1. FAR 61.15(e) – 60-day rule to report all Driving Under the Influence (DUI) actions to the FAA;

2. FAR 61.15(d) – FAA enforcement action against all certificates for two DUIs in three years;

3. FAR 91.17 – the 8-hour bottle-to throttle and 0.04% BAC rules; and

4. FAR Part 67 – the medical disqualifying conditions in the medical application, which contain many alcoholic-related parts.

Every pilot who drinks any alcohol should be aware of how his/her particular Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) and central nervous system is affected by alcohol. Of course, a pilot who drinks alcohol should not fly an airplane with any alcohol in his/her body. Some pilots may not realize how drinking alcoholic beverages – even occasionally, but never before flying – may be putting their flying privileges in serious jeopardy.

How Our Society Deals With Alcohol Is Changing

Given some relatively recent events, the need for pilots to be aware of the effects of alcohol on their BAC and their central nervous system is more important than ever.

First, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) released a report in 2013 recommending that each state in the country change the BAC limit for a DUI from .08 to .05. If such laws are enacted, many more people will be arrested for DUI violations, and some of these people will be pilots.

Second, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) released the latest version of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) in 2013. (The new publication is labeled “DSM-5,” because it is the fifth version of APA’s diagnostic manual.) DSM-5 contains major changes to the medical profession’s approach to alcohol-related health issues.

Third, the “Pilots Bill of Rights,” enacted in 2012, includes a section dealing with potential changes to the medical certificate application and process. Although the new law does not specifically mention alcohol, pilots should monitor this aspect of the legislation to see if new alcohol-related rules are forthcoming.

Given the ongoing and changing focus on alcohol and its use in our society by NTSB, APA, the FAA, and local law enforcement agencies, it is very important for every pilot who drinks any alcohol to know as much as possible about the “legal limits” and his/her “personal limits.” The best way to gain this knowledge is by owning and using a device, which accurately measures your BAC on an individual and immediate basis – a “Breathalyzer.”

The Medical Certificate

Medically, there are three ways for the FAA to keep a pilot who drinks alcohol from flying. First, the FAA has the authority to deny or defer a pilot’s application for a medical certificate. Second, the FAA has the authority to suspend or revoke an existing medical certificate. Third, the Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs) require all pilots holding valid medical certificates to stop flying immediately if they have a disqualifying condition.

An Aviation Medical Examiner (AME) is authorized to issue a medical certificate immediately upon completion of the examination if he/she concludes that the pilot meets the FAA’s medical standards. If the AME determines that the pilot does not meet the standards, the AME can deny certification. In addition, an AME may defer issuing the certificate and forward the application to the FAA’s Aeromedical Certification Division. If the application is deferred, FAA personnel in Oklahoma City will decide if the pilot meets the medical standards.

Even if the AME issues a medical certificate immediately after examining a pilot, the FAA retains the right to deny the application and reverse the AME’s decision within 60 days of the issuance of the medical certificate. If a medical certificate is more than 60 days old, and the FAA decides that the pilot is medically disqualified, then the FAA can take steps to either suspend or revoke the medical certificate. Moreover, don’t forget that pilots with disqualifying conditions must automatically stop flying. According to 14 C.F.R. § 61.53(1), no person is allowed to act as a flight crewmember if he/she, “knows or has reason to know of any medical condition that would make the person unable to meet the requirements for the medical certificate necessary for the pilot operation. . . .” In other words, a pilot who meets the criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence may: (1) have his/her medical application denied/deferred, (2) have his/her medical application revoked, or (3) stop flying as required by 61.53.

The FAA definition of alcohol abuse as a disqualifying medical condition is significantly different from the medical criteria used by doctors who deal professionally with persons who appear to have substance abuse problems. As a result, a pilot may not qualify for a medical certificate due to alleged alcohol abuse, under circumstances where a doctor specializing in mental health and substance abuse would not diagnose an alcohol abuse condition.

The FAA Definition of Alcohol Abuse

The FAA considers a history of either “substance abuse” or “substance dependence” as disqualifying medical conditions. In other words, it may be deemed illegal for a pilot to fly if he/she knows or has reason to know that he/she engaged in misuse of alcohol – even if he/she is currently holding an otherwise valid medical certificate. Item 18 of the medical application begins with the question: “Have you ever in your life been diagnosed with, had, or do you presently have any of the following. . . ?” For each subpart, the airman must answer “yes” or “no” by checking the appropriate box.

Subpart 18(o) requires each applicant to report any “alcohol abuse” to the FAA. In other words, pilots who have ever engaged in “alcohol abuse” are supposed to answer “yes” on the medical application, even if they have not been diagnosed with an alcohol abuse disorder by a medical professional. (“Have you ever in your life . . . had, or do you presently have . . . alcohol dependence or abuse. . . .”)

(Remember, any false or incorrect answers to a question on any FAA form may be grounds for disqualification, and even criminal prosecution.)

What is alcohol abuse?

How does a pilot determine whether he/she should answer “yes” or “no” to subpart 18(o) of the medical application?

What will happen to a pilot who answers “yes” to subpart 18(o)?

What will happen to a pilot who answers 18(o) “no,” and the FAA decides that the pilot should have said “yes”?

The answers to these questions are found in Parts 61 and 67 of the FARs.

According to 14 C.F.R. § 67.107(b), “substance abuse” is defined as the use of a substance (including alcohol) within the preceding two years in a situation in which that use was physically hazardous, if there has been at any other time an instance of the use of a substance also in a situation in which that use was physically hazardous.

Arguably, performing any physical activity after consuming a small amount of alcohol could be considered hazardous, and therefore, alcohol abuse. This might even include swimming, riding a bicycle, or using a lawn mower after drinking a beer. Also, any minor injury suffered after drinking some alcohol (even a slip and fall accident) could be considered evidence of “substance abuse.” According to the FAA, such conduct could end a flying career.

When Is Alcohol Consumption Hazardous?

It should be recognized that the FAA definition of alcohol abuse does not include intoxication or any other measure of impairment. This begs the question: Is the phrase “physically hazardous” limited to intoxication, or does it include lower levels of impairment? In other words, would the FAA agree that all physical activities at BAC levels below intoxication are not “physically hazardous? “ Even low levels of alcohol in the body impair human health and performance. The ingestion of alcohol has an effect on virtually every system in the human body, but the most obvious is the impairment of the central nervous system (CNS).

Alcohol is considered a CNS depressant. Once ingested, alcohol is absorbed into the blood quickly, passing directly through the walls of the stomach and the small intestine. Once in the bloodstream, the alcohol is carried quickly to the brain.

Everyone knows that consuming too much alcohol causes intoxication. However, it is difficult to know how much alcohol is “too much” because alcohol affects people in different ways based on a wide range of variables.

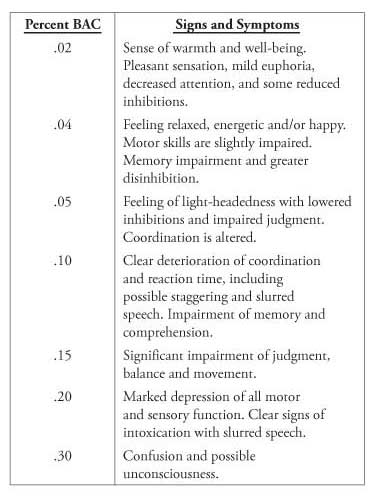

Generally, a beverage with approximately one-half ounce of pure alcohol (a 12 oz. beer, a 5 oz. glass of wine, or a shot of 80 proof distilled liquor) will raise the BAC by approximately 0.02% to 0.03%. However, the individual effects of consuming alcohol are influenced by many significant variables such as age, body weight, gender, rate of consumption, total consumption, prior food intake, fatigue, stress, interaction with other drugs or medicines, etc. Alcohol is metabolized in our bodies at a fairly constant rate. If a person drinks faster than the alcohol is metabolized, the alcohol accumulates in the body, resulting in increased levels of alcohol in the blood.

Below is a table describing the signs and symptoms of alcohol at various BAC levels:

It is important to understand that any pilot who might drive a car after drinking some alcohol may be considered having engaged in alcohol abuse. Although drinking and driving is not the only hazardous conduct used to identify “alcohol abuse,” it is probably the most obvious. As for drinking and driving, getting caught doesn’t matter. Under the FARs, any drinking and driving could be considered abuse – even for the pilot who has never been caught and charged with a DUI.

Whether any activity is hazardous when combined with the consumption of alcohol depends on a large number of variables including: what type of activity (i.e., flying versus walking), and how much alcohol is involved. With that said, it seems clear that the FAA may call a particular activity “hazardous,” while others may disagree.

The Diagnostic & Statistical Manual

For decades, the American Psychiatric Association has published and updated its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (“DSM”). DSM-IV (recently replaced by DSM-5) defined substance abuse as:

A maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by one (or more) of the following, occurring within a 12-month period:

1. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, home (e.g., repeated absences or poor work performance related to substance use; substance-related absences, suspensions, or expulsions from school; neglect of children or household).

2. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous (e.g., driving an automobile or operating a machine when impaired by substance use).

3. Recurrent substance-related legal problems (e.g., arrests for substance-related disorderly conduct).

4. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance (e.g., arguments with spouse about consequences of intoxication, physical fights).

For the majority of people who fit the DSM-IV diagnosis of “alcohol abuse,” the triggering factor was No. 2 – “physically hazardous” situations. The most common situation supporting an alcohol abuse diagnosis was recurrent drinking and driving. (Remember, under the FAA criteria, a pilot is medically disqualified for drinking and driving twice in his/her life.)

The DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse have been widely recognized and applied not only in clinical settings, but are also used extensively in research and for reporting statistical data.

Both the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) and the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) contained questions derived from the DSM-IV criteria in order to assess the prevalence of alcohol-related disorders in the United States.

Several studies have been conducted to examine whether alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence represent distinct disorders, or whether abuse is just an early stage of dependence.

The studies show that alcohol abuse is an acute, rather than a chronic disease, distinct from dependence.

For instance, most persons diagnosed under the DSM criteria with alcohol abuse are unlikely to become alcohol dependent. The studies also show that persons originally diagnosed with alcohol abuse were less likely to exhibit symptoms of abuse at follow-up.

As a medical diagnosis, it is more difficult to identify alcohol abuse than alcohol dependence. Numerous studies have indicated difficulties applying the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse in clinical and related situations.

A key difficulty involves the meaning of the word “recurrent.” DSM-IV does not define “recurrent.” One study using the DSM-IV approach to alcohol abuse chose to define “recurrent” as driving after drinking four times or more within a one-year period. Some researchers doubt whether such behavior is sufficient or appropriate for making the diagnosis of a mental disorder.

Some medical experts have argued that alcohol abuse should not be classified as a mental disorder based on evidence of driving after drinking when this behavior does not occur in conjunction with other alcohol-related problems. These experts are not convinced that drinking after driving – while obviously unwise behavior – is the proper basis for a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder.

DSM-5 takes a completely new approach to alcohol-related medical conditions. In fact, DSM-5 abandons the separation between alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence. At this time, it is unclear whether the analysis of the FAA alcohol-related medical rules will be influenced by DSM-5.

In summary, it is obvious that the FAA and the APA use drastically different situations and factors for identifying people with alcohol-related mental disorders. For pilots in the United States, the only rules that govern their flying privileges are those issued by the FAA – even if they do not conform to guidelines issues by other medical professionals. Do you believe that two instances of “abuse” of alcohol in a lifetime is a medical condition, which should disqualify a pilot from holding a medical certificate? Regardless of your beliefs, the FAA criteria for alcohol abuse as a disqualifying medical condition is “the law.” As far as I can tell, the rewrite of the medical application required by the Pilot’s Bill of Rights, will not include any major changes to the FAA’s approach to “alcohol abuse.”

Under these circumstances it is important for pilots to understand how drinking alcohol could cost them their flying privileges. To better understand your particular situation – if you drink alcohol – you should probably own a Breathalyzer.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Russell A. Klingaman is a panel attorney for the AOPA legal services plan, and the president of the Lawyer Pilots Bar Association. Additionally, he is a member of EAA, NBAA and many other aviation organizations, and teaches aviation law at Marquette University and UW-Oshkosh. Klingaman is an active pilot, an aircraft owner and a partner in the law firm of Hinshaw & Culbertson LLP in Milwaukee, Wisconsin: 414-276-6464, rklingaman@hinshawlaw.com.