by Rachel Obermoller

AvRep, MnDOT Aeronautics

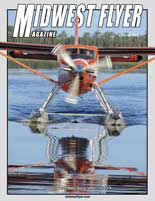

Imagine perfectly smooth water, without a ripple and reflecting a mirror-like image, the slightest bit of steam rising from the warm water into the cool morning air. There is little more you need to add other than a peaceful sunrise, mug of steaming coffee, and the call of a loon from the middle of the lake to imagine the most quintessential and iconic “Up North” experience. Yet for a seaplane pilot, glassy water presents challenging water conditions and optical illusions, which pose significant hazards.

A former private pilot student of mine, Jonathan DeVall, is now serving as a missionary pilot in Brazil, and uses a seaplane to transport people and supplies where there are no roads. Jonathan has a keen eye for photography in addition to being an excellent pilot and has shared many photos and videos of his adventures, including quite a few which capture completely glassy water and the undistorted reflection of the objects above. His experiences in Brazil have given him the opportunity to practice his glassy water technique often, as many days, there is little wind to manipulate the surface of the water enough to provide the necessary depth perception.

Glassy water can be present across a broad spectrum, from a crystal clear mirror-like surface, to rippled or even wavy water, which reflects a distorted image. The reason it presents such a challenge for seaplane pilots is that without texture on the surface of the water, there is no good way to judge height. The pilot has the illusion he is higher than he actually is and in this condition, flaring using a normal technique does not work, as the pilot would touch down much sooner than expected. For this reason, we must use a glassy water technique, the equivalent to an instrument approach procedure for the seaplane world.

A glassy water landing requires the pilot establish a nose up attitude prior to the loss of outside visual reference, such as crossing the shoreline of a lake or descending below the treeline when landing in a river. Establishing the appropriate nose-up pitch attitude and airspeed, and controlling the rate of descent using power, should be accomplished before this loss of outside visual reference. If this is not accomplished, a go-around is necessary to avoid succumbing to the illusion of glassy water. The lack of a stabilized approach at the appropriate time is just one condition that requires a go-around during a glassy water landing.

Because we are making our approach with power and using a shallow rate of descent, a glassy water landing will require significantly more distance than a power-off landing. For this reason, it is important to establish a go-around point, and if the aircraft has not touched down by this time, we need to execute the go-around and re-evaluate the situation.

Choose a point for the go-around, which leaves sufficient water to stop the aircraft and also allows for terrain clearance during the go-around. A small body of water or tall obstacles to clear at the shoreline can make a glassy water landing difficult, and in some situations, a lake which is large enough on a normal day may prove too short to land on in glassy conditions. Thankfully, there are some tricks we can use to shorten the required distance to land on glassy water days.

Normally, glassy water exists when there is no wind, which makes the landing direction less important than it would be on a windy day. If the water body has obstacles along the shore, elect to cross the shoreline where they are shortest. This minimizes altitude to lose using the glassy water technique after the loss of outside visual reference, therefore minimizing the water length required for the landing. Maintaining outside visual references as long as possible by flying parallel to a shoreline and keeping it in your field of vision and being proficient at transitioning to the glassy water configuration efficiently, help to minimize the landing distance necessary. It should go without saying that when all else is equal, we aren’t concerned about terrain clearance, noise abatement or obstructions under the water, and the water body isn’t a perfect circle, so land in the direction, which maximizes the distance available.

Several times I have flown over a landing site that appeared to have enough texture to accomplish a normal power off landing, yet in the last few seconds before touchdown, the depth perception went away as the water appeared to smooth out and I lost the ability to judge my height above the water. Sometimes this necessitated a go-around, and other times I still had an outside visual reference by which to judge my height above the water with plenty of water in front of me and was able to quickly transition to a glassy water landing. Any time the surface of the water has any reflection, a seaplane pilot is wise to use the glassy water technique; and any time the winds are light, it is also wise to anticipate the need for a glassy water landing.

In addition to posing a risk during landing, glassy water can complicate a takeoff. Because the water is smooth, it produces constant drag against the float on the step, unlike water with waves where the drag is reduced because the water is not in constant contact. Couple this with the absence of wind, and you can see why it takes more water to get in the air. Taxiing through the takeoff area can help create texture on the water, and we can see from Jonathan’s photo that even low-speed taxi creates ripples across the water. There are also other techniques we can employ to maximize the available takeoff distance, but we should always be thinking about our takeoff abort point, even when the water isn’t glassy, much like we establish go-around points during a landing to ensure we can safely stop before the shore or other obstacle.

The glassy water technique is just one of the things a pilot can learn from training for their seaplane rating that can be useful in the other flying they do. The skills needed for glassy water are similar to those needed to fly a glideslope on an instrument approach or establish a stabilized approach to landing on final. A seaplane rating also gives many pilots a new appreciation for the effects of wind, planning and executing docking, ramping, or beaching, and even securing the aircraft.

If you don’t hold a seaplane rating, consider putting this on your flying “bucket list” or find another rating or skill to add to your flying repertoire. I’ve heard many glider pilots say the same types of things, and I’ve always been partial to taildraggers, but those are just a few ideas to get you dreaming. Whatever type of flying you do, make sure to keep your skills fresh, get recurrent training periodically, and brush up on the skills you haven’t used recently. If you are seaplane flying, or your flying in general has taken a vacation over the winter, review the things you need to know and practice the things you need to do to stay safe and sharp in the airplane. A good resource for seaplane pilots to review comes out of the Anchorage Flight Standards District Office in the form of a “Seaplane Ops Guide,” which you can find at https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/avs/offices/afs/divisions/alaskan_region/media/Seaplane_Guide.pdf

Keep the tips up, and don’t forget the water rudders!