Story by Jim Karpowitz

Story by Jim Karpowitz

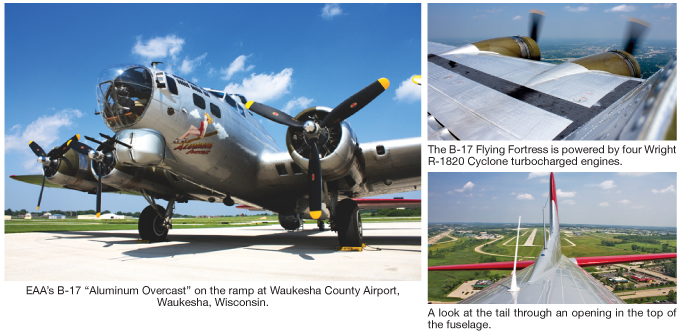

Photos by Geoff Sobering

There are few things that the boss could say to me during a workday that would brighten it more than, “I was supposed to fly in the B-17 tomorrow, but I can’t make the flight; do you want to take it?” Well, maybe “I’m doubling your salary,” or “You look tired; you should really take the rest of the month off,” could edge out such an offer, I suppose. Since childhood I’ve been fascinated by large, round-engined propeller-driven airplanes. Imagine the stories that the B-17G could tell, not only of its wartime service, but more recently of the countless wonder-filled faces of people who have been fortunate enough to fly in the big bird. Tomorrow, June 24, 2010, I would be taking a ride aboard “Aluminum Overcast,” the flagship bomber of the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA).

Being a lifelong radio buff (34 years as a licensed ham operator and nearly 23 years in avionics), I knew exactly where I wanted to sit in the airplane – in the radio room position. Located just aft of the bomb bay in a compartment roughly equal to a half-bathroom, it was the avionics bay of the 1945-era aircraft. I say “was” because the large, heavy boxes and the imposing antenna tuning array, including the Frankenstein-style knife switch and retractable antenna, have long passed into disuse. All of this vintage equipment was designed to function on High Frequency (HF), the only practical means at the time to achieve long distance communication. Operating it was more art than science and would keep the radio operator more than mildly occupied during the course of a mission.

Seeing all of this gear takes me back to one of my great regrets in life. When I was about 10 years old, I happened upon a rummage sale where a fellow was selling a massive load of vintage radio equipment, including old military tube-type gear. I had already developed an interest in old equipment and a fairly good working knowledge of radio, so this was a gold mine. Unfortunately, my limited budget and the fact that you can only carry so much on a bicycle meant that I had to limit my purchases that day. Had I really understood what I was looking at, I would have begged my dad to go buy the guy out. I’ve never seen a collection like that before or since. A BC-610 would have looked nice in my collection, but hey, we live and learn.

So anyway, there I was the next day, seated in the radio room, listening to the chatter over the rumble of four thirsty Wrights, checking over my camera gear and taking it all in. The radio room is strictly for show and tell these days. The airplane is now equipped with a modern Garmin stack occupying part of an instrument panel modified to accommodate equipment that would have been beyond anyone’s wildest dreams 65 years ago. What a study in contrasts. This old HF gear gulped a relatively huge amount of power, took a great deal of skill and finesse to operate (much like the aircraft itself) and was very much at the mercy of atmospheric conditions. And, for the most part, all you did was talk to people and maybe take a directional bearing with it. No VOR, no ILS, certainly no RNAV, no transponder, no DME, no LORAN. These guys back in the day had maps, a compass, the stars and maybe a few stations to catch a radio bearing. Using these comparatively primitive tools, they managed to find the targets, deliver the goods and get back home under some pretty adverse conditions. Thinking about all of this gives me a pretty strong urge to stand and salute the people who made this happen.

The takeoff run gives you an appreciation for soundproofing, of which the B-17 has none. Those four engines are exceedingly loud. In minutes, we were airborne and I could wander around the aircraft. Up to the nose through an access tunnel I went. That access tunnel reminds me of the last time I had to chase my kids in the McDonald’s playland equipment (I don’t fit gracefully through tight spaces and the playland tunnel was roomier). The glass-enclosed nose cone was where the bombardier sat, but this time we were not dodging flak and fighting off pesky little airplanes shooting at us. It’s an amazing sight and I could have sat there for a long time. Other people wanted a look too, so I folded myself back up toward the cockpit, and paused to look over the pilot’s shoulders. Yeah, the boys of World War II would have salivated over even one GNS-430, but ground-based radar was enough of a miracle for that era.

Back aft, I lingered at the waist gunner position. Hmm… I don’t suppose I could take these Browning 50mms to Fletcher’s for a little target practice, could I? Oh, yeah, not many airplanes have an open fuselage where you can stick your hands or your head up in the slipstream. I put my video camera up and ran some tape on the view. Before long, we’re given the signal that it’s time to secure for landing.

Soon, we’re back on the ground and the thunder returns to a rumble so we don’t have to shout anymore to be heard. After we disembarked, I took some time to listen to Douglas Holt, a World War II vet, relate some of his wartime recollections and then it was back to work.

My flight of the B-17 was a perspective adjustment. This airplane represents the best of a bygone era. Faster, more capable and higher-tech bombers (and ordnance) exist today, but show me something built in the last 30 years that can make an octogenarian cry at the sight of it. As I listened to just a few of Doug’s stories while contemplating the equipment that these guys were using, I understood that flying this bird took a unique combination of skill, fortune and courage. If the crews of the B-17 had the small radio stack that the aircraft has today, to say nothing of the extremely sophisticated current military technology, World War II might have been a very different engagement. At the same time, what the B-17 and its relatively primitive avionics bay may have lacked in technology, it more than excels in pure elegance and character. I cannot help but have a great deal of respect for the people who knew how to make the radios back then work when it counted the most.

These days, we in aviation are blessed with incredible panel capability and safety systems unheard of even 30 years ago. Perhaps a legitimate concern might be that today’s avionics could potentially lull pilots into complacency. Navigation has never been easier with modern GPS. In my avionics service work, I periodically discover VOR indicators that are substantially out of alignment, undetected by the pilot because the GPS is the navigation of choice. By all means, I think that we ought to utilize the wonderful capabilities that the modern panel has to offer, but the challenge is to maintain our skills and use these avionics as tools and not a crutch. As I said, the B-17 crews found their targets with a map, a compass, a watch and a Norden bombsight. How many of us today could do the same in our current state of proficiency?

EDITOR’S NOTE: Jim Karpowitz is the avionics support technician at Skycom Avionics, Inc., located at Waukesha County Airport, Waukesha, Wisconsin.