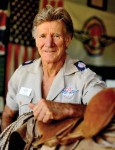

NASHVILLE, TENN. – At the National Association of State Aviation Officials’ (NASAO) 80th Anniversary Convention in Nashville, Tenn. in September 2011, there was a fascinating speaker by the name of Stan Brock. You may not immediately recognize Stan Brock’s name, but for those of us who grew up watching Mutual of Omaha’s “Wild Kingdom” on Sunday evenings, he was one of its co-stars, along with the show’s host, Marlin Perkins.

Stan was born and grew up in England. He attended public school, but dropped out after a couple of years in high school. Although he planned to return, the spirit of wanderlust prevailed. His father worked for the British government’s Foreign Service and was assigned to the former British colony of British Guyana. With the British government purchasing a one-way ticket to see his father, he arrived in Georgetown, Guyana nearly three weeks later.

While wandering the streets one day, he noticed a sign that said “Dadanawa Ranch.” With his curiosity peaked, he entered the building and inquired about the ranch, and whether or not they were looking for help. After finding out that the ranch was located on the Brazilian border, the bookkeeper informed him that “no one ever goes up to the ranch” because it was an austere environment far from civilization. The only people there are natives who tend 50,000 head of cattle on the 4,000 square mile ranch.

Not deterred by the bookkeeper, Stan hopped a ride on an old C-47 that occasionally dropped supplies at the ranch, which was a 25-35-day walk from Georgetown through dense jungle. After hitching a ride on the C-47, he soon found himself on a savanna surrounded by people who only spoke Wapishana. Through gestures and body language, he was able to communicate with the natives that he wanted to work as a cowboy, and that’s when he discovered that the cowboys there were indeed Indians. The natives gave him a new horse named “Kang,” which he later learned meant “Devil” in English. Kang had never been broken, so it was up to Stan to do the job. With the Wapishana and his horse as teachers, he soon learned to be proficient in the trade.

On his first attempt, Kang bucked and fell on top of him. The other cowboys gathered around and offered their verbal assistance, but Stan was convinced that he needed medical help. That’s when he realized that the nearest doctor was in Georgetown…nearly a month’s walk away. Many years later while conversing with astronaut Ed Mitchell, Stan was told that even on the moon, the astronauts were only three days away from medical assistance.

The realization that there was no medical assistance within a reasonable distance convinced Stan that there had to be a better way. Now fluent in the native language, he convinced his fellow cowboys that they should carve out a landing strip and he would go to Georgetown and learn to fly. Taking a horse nine days to the edge of the jungle and walking another 20 days through the rain forest, he made it back to civilization where he started taking lessons in a two-seat Champion aircraft. Shortly after soloing, he was issued British Colonial pilot license #92.

With his certificate in hand, Stan sought out an aircraft he could take back to the camp, along with a drum of gasoline. He found an old Piper Tri-Pacer, which was converted to a tail-dragger, loaded the drum and headed home. He had a total of 30 hours of flight time, including the time it took to return to Dadanawa.

Since there were no navigational aids, he flew at treetop level where he could recognize familiar landmarks. When arriving back at the ranch, he landed and promptly up-ended the aircraft while trying to stop on the 700-800 ft. airstrip that he and the others had cleared earlier. The Wapishana thought that his landing was very good, but then again, they had never seen an aircraft land before. It didn’t take long and work was started to “extend” the runway to accommodate the plane.

With the plane, the 30-plus-day walk now became a 3.5-hour flight. With each trip he brought back medical supplies and soon became the unofficial medic. However, when it was beyond his capabilities, he would transport the natives to Georgetown where they could receive proper treatment. He then set about convincing the British government that there was a need for medical services in the interior of Guyana. After several years of lobbying, he was able to get a senior official with the British Ministry of Health to visit the remote ranch while visiting Guyana. Eventually he was successful in his efforts and thus began the concept of the Remote Area Medical Volunteer Corps (RAM).

Because of his knowledge and reputation as a “bush” pilot and outdoorsman, Stan was brought to Chicago by the producers of Mutual of Omaha’s TV series, “Wild Kingdom.” Chicago was almost a foreign world in comparison to Guyana where he had spent much of his young adulthood. He noted that he was so “uninformed” that he donated some change to a guy along the street for the Black Panthers. He, of course thought that it was an environmental group trying to save another endangered species. The show was successful and Stan remained in the U.S., but his desire to bring better medical access to remote areas remained strong.

In 1985, Stan founded RAM where he continues his volunteer work with the organization that is headquartered in Knoxville, Tenn. RAM is a non-profit, volunteer, airborne medical relief corps that provides free health/dental/eye care, veterinary services, and technical and educational assistance to people in remote areas of the United States and around the world. Earlier in 2011, they assisted over 2,000 inner city residents of Chicago and just recently worked at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation where over 85% of the population is unemployed.

Stan conservatively estimates that over 25% of the U.S. population doesn’t have access to medical treatment. RAM efforts within the U.S. have been hindered significantly by state and local governmental agencies, which insist that the volunteer medical personnel be registered or licensed within their individual state. In Los Angeles, RAM had 100 dental chairs set up for a free clinic, but could only fill 30 because there were not enough volunteer California registered dentists in the Los Angeles area. Dentists from surrounding states were willing to volunteer, but California law prevented them from donating their time and talent. Only Tennessee, Oklahoma and Illinois will allow volunteer medical personnel to provide free assistance without being registered within their state. Stan has tried to get the U.S. government to pass legislation that would transcend state borders, but so far, the federal government has refused to move forward for fear of violating a “state’s rights” issue.

Although there are needs within the U.S., RAM continues to provide medical support around the world including some countries recently devastated by earthquakes and hurricanes.

Our hats are off to people like Stan who have put the welfare of others first. We wish him success in his efforts to get legislation passed that will enable RAM volunteers to provide medical assistance no matter the location.

If you would like to learn more about RAM, please visit their website at www.ramusa.org.