by Mick Kaufman

It seems to be human nature that we all like to play “Monday Morning Quarterback” after an accident or incident. In a recent accident involving a friend’s airplane, I see a possible situation that has occurred too often with non-professional instrument pilots and especially those who usually fly approaches only in an approach control radar environment.

In the last issue, the topic on picking up airborne clearances drew some comments from one of our readers, and I would like to cover this with additional thoughts. Another reader sent me comments from my article entitled “Stay Out of the Ice,” and I would like to address these comments as well.

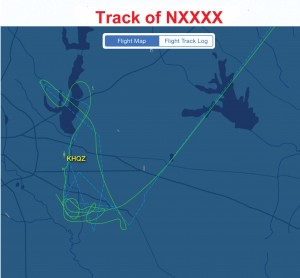

Addressing an issue of getting established on an approach and the lack of knowledge of the procedure shows up quite often when I do an instrument proficiency check (IPC) as a flight instructor. Not wanting to be that “Monday Morning Quarterback” on a fatal accident (FIG 1), and not having heard the ATC tapes, this is nothing more than a lesson for instrument pilots.

When a pilot comes to me for an instrument proficiency check, I avoid taking them to an airport where radar vectors are the norm for getting established on an approach if this is the environment they normally fly in. Understanding radar vectors for an approach is extremely important, but flying the full approach at non-approach control airports can cause extreme stress for a pilot who is not current on flying the full approach procedure.

A number of years ago while instructing a pilot during one of the Baron/Bonanza flight clinics I participated in, one pilot showed me the importance of doing full approaches during training by displaying his lack of knowledge in flying this procedure. The weather the day of our flight clinic was IFR, so we filed to Oshkosh out of Waukesha, Wisconsin for some practice approaches. The departure was routine, and we were given radar vectors for traffic by Milwaukee Approach Control, then told to contact Chicago Center. Chicago gave us an additional vector for traffic, then about 25 miles from Oshkosh, cleared us for the approach. The pilot had no idea where to go or what to do. In the environment he was used to flying in, ATC always vectored him for the final approach. I have seen this situation over and over so many times, but this particular case woke me up. The fact is many pilots do not know how to handle this and an occasional professional falls into this category as well – especially the airline pilot who always fly in an approach radar environment.

When we as pilots look at an approach chart, we should be looking for an Initial Approach Fix; this is always labeled “IAF” on the chart. We want to make sure we do not confuse it with an Intermediate Fix or “IF.” On some charts we may see multiple IAFs, and it is our responsibility to select one that works out best from the direction we are approaching.

A pilot may take the initiative to request a specific IAF from air traffic control (ATC). Example: “Cessna N2852F would like to request direct Dells for the VOR-A approach into Lone Rock.” Sometimes ATC will ask the pilot what approach they would like and what IAF they would like to proceed to. Selecting the approach and the IAF will require some thought – the direction you are coming from, the minimums for the airport, the weather and the winds. After you select the approach, then select the IAF based on direction and the time necessary to do the approach.

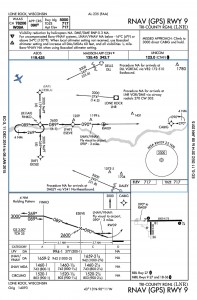

Let’s look at the RNAV GPS 09 LNR approach: (FIG 2). If you are approaching from the northwest, you have two logical choices for the IAF which are CEBLU or FINKO. If you choose CEBLU, your route will become CEBLU to FINKO (FINKO becomes the IF or Intermediate Fix), then you will proceed to ESEVE which is your Final Approach Fix or FAF. If you choose FINKO as the IAF, your route will be FINKO followed by a 4 nm racetrack Procedure Turn (PT). You would be crossing FINKO a second time at the IF before reaching ESEVE, the FAF. My choice would have been to use CEBLU as my IAF and eliminating that 4 nm racetrack Procedure Turn.

Altitudes are factors for the pilot to consider in an approach and knowing what ATC expects from the pilot; it is important for the pilot’s safety as well.

Let’s make the assumption that after confirming the approach you want and the requested IAF, you get the following clearance 25 miles out from ATC: “Epic N410LT, proceed direct CEBLU. Maintain 5000 until established on a segment of the approach. You are cleared to the RNAV/GPS 09 approach to the Lone Rock Airport. Cancellation on this frequency or on the ground with flight service.” After reading back your clearance, you are to proceed to CEBLU and the lowest altitude to that point is 5000 feet. After crossing CEBLU, there is a published altitude of 3000 feet, which you can descend to only because of the controller’s words, “cleared to the approach.”

I have mentioned above that most approaches have multiple IAFs, and you may request one that seems to fit your needs; ATC may assign one as well. If ATC assigns one, it is usually based on traffic or it could even be based on weather.

Another interesting concept while navigating for an approach is the transition. FIG 2 has several published transitions for this approach; one from the DLL VORTAC and one from the LNR VOR. In simple terms, a published transition is a route that leads you to the IAF and is easily distinguished by showing a published altitude.

There seems to be some confusion on transitions from pilots as well as controllers, as I have seen in my own flying experiences.

On an instrument flight from Eagle River, Wisconsin (EGV) to Lone Rock (LNR) while approaching the DLL VORTAC from the north at an altitude of 6000 feet, I was cleared for this approach via the Dells transition. After crossing the DLL VORTAC, I began a descent and was immediately questioned by ATC stating that I had not been given a lower altitude. My response was that you had cleared me for the approach; there was no more said after my response.

One last point to make on this topic is that there are some approaches that do not have even one IAF from which to begin the approach. In the case of no IAF as in the ILS/LOC 22L at KORD, RADAR is always required and is noted on the approach chart.

In my column in the last issue, I covered the subject of getting an IFR clearance airborne after departing an airport VFR. I received a rebuttal letter from one of our readers in Topeka, Kansas, who is a pilot and I believe by his letter that he is or has been an air traffic controller. The reader brought to light an issue that I have failed to mention or teach for a specific reason. The following is a quote published at the beginning of the section on departure procedures (DPs) and is referenced in the AIM 5-2-8 (c)(1):

1. Obstacle clearance responsibility also rests with the pilot when he/she chooses to climb in visual conditions in lieu of flying a DP and/or depart under increased takeoff minima, rather than fly the climb gradient. Standard takeoff minima are one statute mile for aircraft having two engines or less and one-half statute mile for aircraft having more than two engines.

The above quote is referenced in CFM 14 and is referenced to certain operators under FAA Part 91. The interesting item that I failed to mention for a reason is that Part 91 operators can legally depart ZERO/ZERO under the rules, but why would you? The reader brings up a very good point in his letter referring to the pilot, why would he/she embrace “such petty ideas as launching in marginal weather that only test system safety and good judgment.” Strike my comment from the previous issue of flying VFR to an airport with a published DP as a possible solution to making it work. The AIM 5-2-8 (a) below gives us an insight to the purpose for DPs, so why not use them:

a. Why are DPs necessary? The primary reason is to provide obstacle clearance protection information to pilots. A secondary reason, at busier airports, is to increase efficiency and reduce communications and departure delays through the use of SIDs (Standard Instrument Departures).

Thanks to this reader for his comments and suggestions.

Another comment from a reader in St. Cloud, Minnesota about the article I wrote entitled, “Keep Out of the Ice.” The reader quizzed me on two questions regarding icing, starting by answering question number one.

I consider icing in an unprotected airplane one of my top fears, preceded only by an in-flight fire and an engine failure at night in a single-engine aircraft. A pilot at night in a single-engine aircraft. A pilot should not underestimate the fear of thunderstorms; however, Nexrad weather in the cockpit can help the pilot avoid them by a wide margin, and not fly through them. I have been in icing many times flying IFR and declared an emergency on one occasion, as I could no longer hold altitude. Please don’t take frost lightly as I lost two dear friends when they attempted to take off from the Naperville, Illinois airport in January of 2009. The airplane rolled inverted on take-off and caught fire.

The Minnesota reader’s second question is a tough one, asking for a strategy to avoid icing. From my icing article, I state that “any time you fly in visible moisture and the temperature is below freezing, you will get ice.” The question is how much? Sometimes the amount of ice is so minuscule that you couldn’t measure it with a micrometer and at other times it could be an inch in less than a minute. Ice has brought down large military transports and airliners in the past; no one is immune.

Preliminary reports suggest that icing could have been a contributing factor to the recent crash of AirAsia Flight 8501.

The best advice is to look for pilot reports which I find surprisingly harder to get with so much computer provided weather. Next is to make sure there is a safe way to get out of the ice if you should get more than you can handle.

Don’t hesitate to declare a problem to ATC. Ask for help and declare an emergency if needed. In recent years, I have found ATC more helpful when the ice word is mentioned than they did many years ago when I needed to declare an emergency. By the comments in the reader’s letter, I think he already has a great respect for icing. I appreciate hearing from my readers.

Best wishes and safe flying in the New Year!

EDITOR’S NOTE: Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman is a Certified Instrument Flight Instructor (CFII) and the program manager of flight operations with “Bonanza/Baron Pilot Training,” operating out of Lone Rock (LNR) and Eagle River (EGV), Wisconsin. Kaufman was named “FAA’s Safety Team Representative of the Year for Wisconsin” in 2008. Email questions to captmick@me.com or call 817-988-0174.