by Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman

Copyright 2020. All rights reserved!

Published in Midwest Flyer Magazine (online) – December 2020/January 2021 issue

We have all seen our lives change since earlier this year, which has affected aviation to a great extent. There has been little happening in my flight-training arena, and its rules, regulations and procedures have been changing on a daily basis because of the virus. For those of you trying to find out what has changed, I would recommend calling AOPA as I have done, to catch up on the updates.

Many of the rules dealing with biennial flight reviews (BFRs), instrument proficiency checks (IPCs) and medicals have changed due to the pandemic. This is an extremely difficult time for us as we are truly dealing with a disease we do not understand, and for which even “the experts” do not have conclusive answers. This is a tough one, even for them.

Nonetheless, I have been trying to keep my flying skills sharp and using my airplane as much as possible. But with reduced income due to my flight training business shut down, and my wife working only part-time, there is not any extra money available for proficiency and fun flying without a useful travel destination in mind.

We have a summer home in northern Wisconsin on a lake, and we use our Bonanza to commute for weekends and holidays when feasible. One hour of flying beats 5 hours on the road, and flying is much safer and more enjoyable! Labor Day weekend was one of those great long weekends and on Labor Day, it was a flight back home to southwest Wisconsin.

All forecasts, including the aviation forecast, showed good VFR weather. I started monitoring the weather forecasts several days in advance. For those who do not use ForeFlight, a feature was added about a year ago giving pilots a longer-range forecast than a Terminal Area Forecast (TAF); it is labeled Model Output Statistics (MOS).

Our plan was to depart for home about 3:00 pm. I did a final check of the weather at about 1:00 pm and everything was looking great for a VFR flight home. Upon reaching the airport after a short 10-minute drive, we loaded the plane, did a preflight inspection, fueled up, climbed in, and taxied for departure. After taxiing to the run-up area and completing my checklist, I decided to do one last weather check.

I have both my iPad with ForeFlight and a Garmin Area 660 connected to a Garmin GDL-52, which are capable of displaying both Sirius XM and ADS-B weather. I have always been a big fan of Sirius XM weather over ADS-B weather, and it is great to get it on the ground, even though the iPad can access it from cell signals on the ground wherever service is available.

What I saw on my iPad was a line of storms starting to develop from east to west about one-third of the way from my departure point at Eagle River, Wisconsin (KEGV). This cannot be happening, I told myself as I went to the weather screen on the Garmin 660, but it confirmed the same indication. Regardless, I decided to launch and watch the weather closely as I headed south.

After departing, I could see that the weather was not looking good as this line was becoming solid and intensifying. I was not the only pilot caught off guard, as many pilots fly to vacation homes on weekends and then return home for the work week. I saw more than six aircraft on ADS-B flying parallel to this line of weather, looking for a path to get through as the line was only about 30 miles wide, and it was now solid. As I passed Rhinelander, Wisconsin, about 30 miles into the flight, I decided to make a 180-degree turn and head back to Eagle River.

This is what “aeronautical decision-making” is all about, and “human factors” also played a part in this as well, as my wife was scheduled to work the next morning. The FAA puts both of these factors into the training syllabus as special emphasis areas. The FAA also claims that we should teach these factors as flight instructors for which I disagree partially. We cannot teach good judgment, but we can surely influence good aeronautical decision-making and make pilots aware of the human factors associated with using good judgment.

As a member of the FAA Safety Team (FAAST), I developed a power point presentation called “Hold My Beer and Watch This” to make pilots aware of the hazardous thought patterns that affect all of us. In this article, I would like to reference a few other incidences that occurred during my many years of flying airplanes in which these two factors work together.

I was an instructor and charter pilot in the late 1970s and early 1980s working for a fixed base operator. I had a flight to Fort Dodge, Iowa early one morning – a flight I had made many times before for the same customer. Arriving early at the airport, I checked weather with the flight service station and decided to cancel the flight due to weather. I called the customer to inform them of my decision and they decided to drive.

A few minutes later my boss arrived and asked why I was not getting the airplane ready to go. I told him that I cancelled the flight due to the weather. His comment was “Call the customer back” – which I did – that he would take the flight. The customers arrived and my boss departed for Fort Dodge, only to return several hours later after shooting the approach three times and unable to get in.

My boss sent the customer a bill for the flight, which they paid, but never did a charter with his company again. About a year later that customer purchased their own airplane and hired me as their pilot. Sadly, my former employer was killed about a year later in an airplane accident. We can see how both aeronautical decision-making and human factors may have played in this incident.

In 1992, I decided to specialize in training pilots for their instrument rating and worked as a contract employee for PIC (Professional Instrument Courses). One of my assignments was to train a pilot from Wisconsin for his instrument rating. This pilot had a Piper Arrow and was a good student as far as the training went, but he was financially stressed to afford his airplane and the cost of the training.

Some years later it was reported on the news that four Wisconsin residents were killed in a fatal airplane accident in Illinois. I felt compelled to follow the investigation when I learned that the pilot had been this student. The conclusion of the investigation was as follows:

The pilot, his fiancé and his son and his son’s newly engaged fiancé were returning from a vacation in Florida where his son became engaged at Disney World. They were on an IFR flight plan where he successfully shot an instrument approach at an Illinois airport. The pilot asked the fixed base operator the gas price and decided not to purchase fuel, bought a soda and filed IFR to another airport about 50 miles away. On the instrument approach to the next airport, the airplane ran out of gas and crashed. I was so saddened by his decision-making process but can reference many other situations that became statistics because of fuel price shopping and fuel starvation.

This again goes back to human factors, as most of us are guilty of stretching the miles to get cheaper fuel, both in our cars and our airplanes. I paid $15.00 per gallon U.S. for avgas in Deer Lake, Newfoundland two years ago, but running out of gas over water would not have a good ending. When we check fuel prices on our ForeFlight app, we often see airports in the U.S. a few miles apart with several dollars per gallon difference in price. Fuel starvation due to fuel prices is a high price to pay, compared to paying more at the pump.

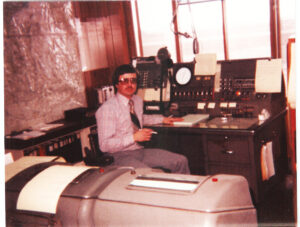

Up until the mid-1980s, Wisconsin had numerous flight service stations (FSS) throughout the state, and one of them was at Tri-County Regional Airport in Lone Rock, Wisconsin (KLNR).

On one rather nasty weather day, I was in the FSS getting a weather briefing for a flight the next day when an aircraft landed unannounced on the radio. The pilot was not instrument rated and flying VFR from Minneapolis to Chicago, and it was obvious by the tone of his voice and the current weather conditions in the area that he had been in trouble.

Henry Luxem was the FSS specialist that was on duty at the time. Henry was a military helicopter pilot and an experienced airplane pilot as well. He talked with the distressed pilot and his passengers about the weather and the fact that the pilot had landed with no radio communications, and therefore violated the airport’s control zone. The pilot then thanked Henry for the information and asked for a weather briefing for his continued flight to Chicago. It is the responsibility of the FSS briefer to only give a briefing, but not any advice to pilots.

As I stood there, I observed the lady passenger nagging the pilot to get going as she needed to get home to her kids. The pilot knew things did not look good weatherwise but was starting to cave into the pressure by the nagging passenger.

Henry may not have been following protocol, but he saved four lives that day. His comment to the lady was, “If you takeoff in this weather, you may never see your kids again, and I will file an airspace violation against the pilot if you takeoff.”

We can again see from this situation how aeronautical decision-making and human factors played out. Henry turned off the lights at the Lone Rock Flight Service Station for the last time on May 4, 1983 and became an air traffic controller at Dane County Regional Airport (KMSN) in Madison, Wisconsin, and then transferred to the Green Bay Flight Service Station a year later, where he finished his career with the FAA.

A few years ago, I gave Henry his seaplane rating in Eagle River, Wisconsin. The old Lone Rock Flight Service Station had been in operation from 1928 to the time of its closing and is now a popular fly-in restaurant.

We can all make mistakes in judgment but understanding decision-making and human behavior can affect our safety and the lives of our passengers.

All scarry situations and accidents cannot be avoided as in the incident of Taca Flight 110 going into New Orleans (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LFTFCfcnqF8 ). We have mechanical and design flaws that are above what many of us can imagine.

Here are several of my favorite aviation quotes that most of us have heard over the years:

“I would rather be on the ground wishing I was up flying, than up flying, wishing I was on the ground.”

“A superior pilot is one who uses his superior knowledge to avoid situations which may require his superior skills.”

May your next flight be a safe one!

EDITOR’S NOTE: Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman is a Certified Instrument Flight Instructor (CFII) and the program manager of flight operations with the “Bonanza/Baron Pilot Training” organization. Kaufman conducts pilot clinics and specialized instruction throughout the U.S. in a variety of aircraft, which are equipped with a variety of avionics, although he is based in Lone Rock (KLNR) and Eagle River (KEGV), Wisconsin. Kaufman was named “FAA’s Safety Team Representative of the Year” for Wisconsin in 2008. Email questions to captmick@me.com or call 817-988-0174.

DISCLAIMER: The information contained in this column is the expressed opinion of the author only, and readers are advised to seek the advice of their personal flight instructor and others, and refer to the Federal Aviation Regulations, FAA Aeronautical Information Manual and instructional materials before attempting any procedures discussed herein.