by Richard Morey

© Copyright 2024. All rights reserved!

Published in Midwest Flyer Magazine February/March 2024 Digital Issue

The “forward slip” was once a common and essential skill for pilots. Unlike more modern aircraft, general aviation airplanes of the post WWII era often had no flaps or if they did have flaps, they were often ineffective. Pilots of those aircraft used forward slips as pilots today use flaps.

As we know adding flaps increases drag, allowing an aircraft to descend at a greater rate without increasing speed. A properly executed forward slip does the same. Today pilots who fly those older aircraft still utilize forward slips to good advantage. Our new generation of pilots, trained on aircraft with effective flaps, seldom use forward slips as they generally are not needed. Most private pilots learn forward slips as part of the private test standards and once the checkride is over, tend to forget about them. This article will examine the advantages and disadvantages of forward slips. We will review how to set up a forward slip, and when it makes sense to use one.

My fondness for forward slips goes back to the early 1990s. Our family’s fixed base operation was approached to fly freight from Middleton, Wisconsin to the Chicago area. The contract was lucrative enough that my father added two single-engine aircraft on our charter ticket and trained three relatively new flight instructors to fly the route. I was lucky enough to be one of the pilots chosen. The three of us spent a great deal of time in preparation for both the knowledge and flight portions of the checkride. I was still running the shop at that time. My knowledge of aircraft systems as an A&P technician and IA certainly came in handy in our study sessions.

We were flying both a Cessna 172RG (retractable gear) and a fixed gear Cessna 182 Skylane. The checkride was to be in the 172RG. On a side note, the 172RG/182RG retractable landing gear aircraft in my opinion is simply the best single-engine retractable system Cessna ever made. It is elegant in its simplicity, reliable, and very easy to rig and maintain. Like any other aircraft system, it does, however, need proper maintenance.

The day of the checkride finally came. The ground knowledge portion had gone well or at least as well enough that all three of us had progressed to the flight portion. I had been cautioned about who we would be flying with. Our Principle Operating Inspector (POI) was known for her directness. She was not at all reluctant about pointing out any perceived deficiencies in detail. I learned on the flight that she also had a wicked sense of humor.

The flight portion was almost over. My maneuvers met test standards. I had pumped the gear down with no problem. I was beginning to relax. I was on downwind for a short field landing, about to throttle back opposite the point of touchdown, when she pulled the power to idle and informed me that we were instead doing a power-off 180-to-accuracy landing. This maneuver is in most pilots’ estimation, the most difficult of the commercial maneuvers. Landing short, long or having to go around, will get you a pink slip on your commercial checkride.

With this in mind, I trimmed for best glide. I remember my focus was not to be low, so of course I rolled out high on final. Full flaps down and I knew I was going to be long. Without conscious thought, I transitioned into a forward slip. The added drag steepened my descent. I kept the forward slip in until round out and made the landing within tolerances.

As we taxied back, I was treated to an assessment of my landing: “Mr. Morey, aren’t forward slips with full flaps NOT RECOMMENDED in a 172?” I replied that they indeed were not recommended. I was prepared to justify my actions with the “In case of an emergency, the pilot-in-command may deviate from the regulations to the extent necessary to meet that emergency,” but was saved the trouble. For the first time on the checkride, I saw my POI smile. Her voice softened, and she said, “They sure work well though.”

What exactly is a forward slip?

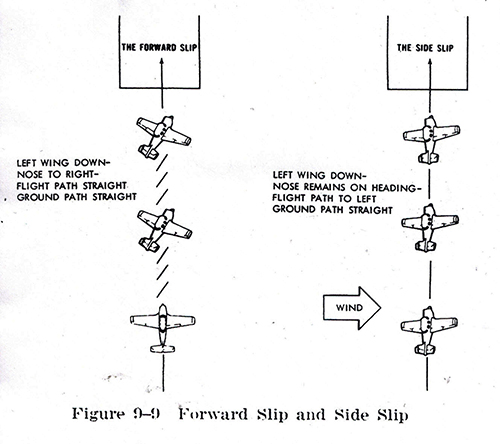

My favorite albeit obsolescent advisory circular, AC61-21A, defines a forward slip as “…a descent with one wing lowered and the airplane’s longitudinal axis at an angle to the flightpath.” Furthermore, the forward slip “is a slip in which the airplane’s direction of motion continues the same as before the slip was begun.”

Think of the airplane “slipping” through the air in the direction of the lowered wing. In a forward slip, the airplane is slipping forward. Side slips have the aircraft slipping sideways through the air ideally offsetting the crosswind drift. Please see the illustration from AC61-21A, as it is much easier to understand the drawing than my written description.

Slips are uncoordinated states of flight, and as such add drag. This additional drag should be kept in mind when performing ether slip. Also keep in mind that some pilots find flying in an uncoordinated manner to be uncomfortable. Practice will help pilots become more accustomed to this.

To enter a slip, one lowers the wing on the side one chooses to slip towards. If there is a crosswind, it is best practice to lower the upwind wing. As you lower the wing simultaneously and smoothly apply the opposite rudder, I teach my students to apply full rudder and control the ground track by varying the bank angle with ailerons.

The FAA cautions pilots to not over speed the aircraft and raise the nose when establishing the forward slip. My experience as a flight instructor has been that students tend to pull back on the yoke when entering a slip. This results in slowing the aircraft beyond best glide. Sufficient to say that attention should be paid to the aircraft’s attitude and a safe airspeed must be maintained when slipping the aircraft. I advise my students to hold 5 knots above their normal approach speed when in a slip in order to be safe.

Airspeed indications may well be off during any slip due to relative wind being at an angle to the pitot tube, and pressure being lower or higher than ambient on the static source in a forward slip. If the static source is on the wing high side of a forward slip, relative wind is impacting the static source which increases the pressure sensed slightly. If the static source is on the wing low side of a forward slip, then there is a slight relative vacuum around the source reducing the sensed pressure. Adding 5 knots to best glide or approach speed may have us err on the side of caution, but the extra speed helps to avoid a low-altitude cross control stall.

At a recent VMC club meeting, a student pilot asked me if there was an altitude below which you should not initiate or maintain a forward slip. My response was typical of most flight instructors I know, “it depends.”

The altitude at which a pilot enters and exits a forward slip is completely dependent on pilot proficiency. I am quite comfortable holding a forward slip through glide, round off and flare, then aligning the longitudinal axis of the aircraft with the direction of flight just prior to touchdown. This is accomplished by leveling the wings and pulling the nose of the aircraft to the desired position with rudder. The FAA suggests simultaneously relaxing the rudder being held… I suggest simultaneously pulling the nose straight with opposite rudder. Applying rudder to pull the nose is a more positive control input and seems to work better for my students. Adjust the pitch attitude to attain the approach speed desired. Less experienced pilots would be well advised to enter and exit a forward slip at higher altitudes.

To practice forward slips, I suggest spending time with an instructor. I start my students at 2500 feet above ground level or higher, an altitude at which we could recover from a stall at least 1500 feet above ground level. Using a ground reference, such as a long straight road or distant broadcast tower, I first demonstrate the maneuver. A power-off glide is established and initially at least no flaps are extended. The forward slip is entered by smoothly banking one wing and smoothly and relatively slowly adding opposite rudder to maximum deflection and holding it. Directional control is now dependent on bank angle. By pointing out that the natural tendency is to raise the nose, and how to adjust the pitch to increase normal glide by 5 knots, it shows the student both what to expect when they enter the maneuver and how to adjust.

We practice entering the forward slip, gliding in a forward slip, and exiting the forward slip by leveling the wings and aligning the nose of the aircraft on the reference point. Only when the student is comfortable in these three phases of the maneuver, do we move on to pattern work.

Instructors should pay close attention to the airspeed and not allow the student to stall the aircraft. A forward slip has one advantage over flaps, in that you can come out of a forward slip at any time. Once flaps are extended, manufacturers recommend leaving them down unless you are going around. Pulling flaps up while gliding results in sink. Coming out of a forward slip does not.

As on my checkride, a forward slip can come in very handy in getting into a tight landing spot. With modern aircraft that have effective flaps, you should simply go around if you find yourself too high on final. In an emergency situation, where going around is not an option, a forward slip may allow a safe landing, rather than running off the end of a runway. To be clear, I do not advocate going against manufacturers’ recommendations. FYI, Cessna advises against using slips with full flaps in 172s. My understanding is that forward slips place a significant side load on the 172’s flaps. I have also been told that it is possible to wash out the airflow over the horizontal stabilizer and elevator if in a forward slip with full flaps down, again in a 172. This would result in an elevator stall. During an elevator stall, the aircraft’s nose will drop rapidly much like a normal stall, only the ailerons will still have authority. To recover, simply transition out of the forward slip to coordinated flight. This will restore the airflow over the tail and bring the noise back up.

In summary, a forward slip is used to add drag to an airplane during a glide to landing. This results in a steeper angle of descent without increasing airspeed. A forward slip is entered by smoothly lowering one wing and smoothly applying full opposite rudder. Care should be taken to establish and maintain a safe approach speed. I recommend adding 5 knots to your normal approach speed in order to compensate for possible inaccurate indicated airspeed due to the slip.

Practice forward slips first at altitude and with a flight instructor. The advantage of forward slips over flaps is that you can come out of a forward slip at any time. Finally, if a go-around is possible, it should be initiated as soon as it is clear that you are higher than you should be on final approach. If you have full flaps extended, do not try to fix an approach that is too high with a forward slip, unless you are very comfortable with the maneuver and your aircraft manufacturer allows it.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Richard Morey was born into an aviation family. He is the third generation to operate the family FBO and flight school, Morey Airplane Company at Middleton Municipal Airport – Morey Field (C29). Among Richard’s diverse roles include charter pilot, flight instructor, and airport manager. He holds an ATP, CFII, MEII, and is an Airframe and Powerplant Mechanic (A&P) with Inspection Authorization (IA). Richard has been an active flight instructor since 1991 with over 15,000 hours instructing, and more than 20,000 hours total time. Of his many roles, flight instruction is by far his favorite! Comments are welcomed via email at Rich@moreyairport.com or by telephone at 608-836-1711. (www.MoreyAirport.com).

DISCLAIMER: The information contained in this column is the expressed opinion of the author only. Readers are advised to seek the advice of their personal flight instructor, aircraft technician, and others, and refer to the Federal Aviation Regulations, FAA Aeronautical Information Manual, and instructional materials concerning any procedures discussed herein.