by Rachel Obermoller

MnDOT Pilot

Published in Midwest Flyer – April/May 2019 issue

What do Swiss cheese, bowties, and trapping have in common? When it comes to aviation, there’s a whole set of tools which use these three seemingly disparate elements to address how we identify, trap, and mitigate risks and hazards.

Most pilots are familiar with the Swiss cheese model used to describe the path to an accident. Essentially, multiple slices of Swiss cheese are placed in front of one another. Each slice is a layer of safeguard, strategy, or operating condition, with holes in different locations. The idea is to trap any threat which penetrates a layer in subsequent layers – if the holes line up and the threat is successful in navigating through all of the layers, an accident could occur. While an abstract idea, it helps to explain the importance of risk analysis. It also conceptualizes how safeguards and procedures protect you and your passengers.

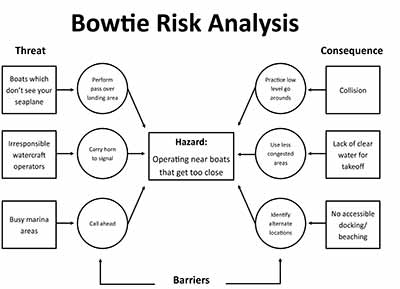

The bowtie risk assessment, or bowtie method, is another tool for considering threats and consequences and applying barriers, or preventive measures, to attempt to mitigate or control the risk of the hazard occurring. Named for the shape of the diagram which is created, the left side considers the threats and barriers to that threat inducing the hazard, while the right side considers the consequences and barriers which prevent the hazard from reaching the consequence stage.

Threat and error management involves identifying a threat or error that occurs, and trapping it to prevent its escalation into an undesired state or outcome. With an ongoing improvement process, the crew must be concerned with not allowing the threat or error to progress, and also prevent the actions they take from creating an additional impact or exposing additional risk. Countermeasures are applied appropriately in the form of both procedural (such as checklist adherence and standard operating procedures) and resources (such as a GPS with terrain awareness and onboard weather and traffic information). Pilots also may employ personal strategies, such as specific skill development and knowledge acquisition.

Risk management is something all pilots should consider, but different types of operations pose very unique risks. Consider a seaplane pilot flying with amphibious floats. Not only can they operate from traditional runways like landplane pilots, but every body of water becomes a conceivable operating location. Seaplane pilots deal with changing conditions on the landing surface, very rarely find themselves with nearby weather reporting, and must contend with the possibility of limited access to emergency services should they need them. Beyond the pilot’s skill, knowledge and planning are the unknowns of the weather, lack of NOTAMs related to their landing sites, and the potential that after sitting on a beach for a weekend, they could find a float compartment full of water or a dead battery and no maintenance personnel anywhere to be found.

Let’s briefly consider the three methods and models detailed earlier as we consider a scenario a seaplane pilot could find themselves in: operating near boats, specifically boats that get too close.

Any seaplane pilot who has operated on a busy body of water (and sometimes those not so busy bodies of water) has experienced boats and personal watercraft whose operators decide it would be fun to get a closer look at a seaplane. Sometimes really close. Sometimes when the seaplane is taking off, landing or during step taxi at high speed. Between the maneuvering limitations of a seaplane and the unknowns of what the boat or watercraft will do, and even whether they see the seaplane, the operational risk can be significant. Let’s start with a bowtie risk assessment of this situation to get a better idea of the threats and possible consequences.

On the left side of our diagram, we can identify several threats, including the following:

• Boats which don’t see the seaplane.

• Irresponsible operators who approach too closely.

• Busy marina areas.

We also need to identify some potential consequences to complete the right side of the diagram. These might include the following:

• Collision between seaplane and boat.

• Lack of clear water for takeoff.

• No accessible docking/beaching location.

Now, we consider what barriers exist or could exist to prevent the threat from being an actual threat (control) or the consequence from occurring (recovery). In this situation, things like performing a pass over the landing area, choosing to operate in less congested areas, or calling ahead to get information and assistance if needed, are all possible barriers.

The Swiss cheese model involves considering the barriers which are in place (or could be used) to prevent an accident. If the goal is to prevent a collision with a boat, possible safeguards might include choosing a less congested operating area, being proficient in accuracy landings, and carrying an air horn for signaling on the water. The Swiss cheese model is less of an analytical method than the bowtie model, but it does help us to conceptually understand how even with safeguards in place, there can still be holes in our efforts which can lead to an accident. This is why it is important to identify and block these threats.

Threat and error management can be applied to real-time operations, as a planning tool, and as a post-flight analytical tool. Using the example we’ve carried through this article, we might have identified the risk of boats in our operating environment before the flight and applied some of the practices we identified earlier to attempt to trap the threat. As the situation progresses, we may identify additional risks we hadn’t considered though, or they may have an impact on the operation in ways we did not predict.

Threat and error management involves identifying those threats, as well as identifying errors we have made, preventing or managing the undesired aircraft state to avert the situation from progressing, and then returning the aircraft to a desirable state. For example, on approach to landing, we may not have enough margin with a personal watercraft which has been operating along the shore, but unpredictably made a turn towards the middle of the lake. Recognizing this, the pilot must react. Initiating a go-around, the pilot prevented the undesirable state from progressing, and once at a safe altitude and correctly configured, has trapped the threat.

In the future, the pilot will likely learn from that situation and give more space to personal watercraft, or avoid situations where they will be presented with similar circumstances. Oftentimes on nice afternoons in the summer, popular lakes can be quite busy. A pilot who has learned this and attempts to minimize the threat, might choose less busy lakes, alternate times of day, or drive themselves to the beach instead of flying.

Many pilots will find that the models, methods, and tools I’ve described are things they are already doing in some form or another. While there are certainly more exciting activities to engage in than sitting around thinking about things that could go wrong, there are plenty of ways to learn from our own experiences and analyze them for continuous improvement.

Learning from others through articles, hangar flying, and studying accident reports and case studies is also an excellent means to improve safety without needing to experience the risk firsthand. And if you’re ever in doubt about whether you’re on the right track, having a seasoned, skilled, and prudent pilot to bounce things off of is an excellent tool. Similarly, a few hours of dual with a qualified flight instructor to brush up on skills that you might rely on in tricky situations, is also time and money well spent. From one seaplane pilot to another, let’s have a great summer of fun and safe flying!