by Dean Zakos

Published in Midwest Flyer – June/July 2020 issue

I just want to keep improving, to keep getting better.” – Anonymous

Scenario: You are level at 3,500 feet. With you in the cockpit are a good friend (a non-pilot) and your eight-year-old daughter.

You have just enjoyed lunch at one of your favorite flying destinations and are headed back to your home airport. ETE is approximately one hour.

Sky is 7,000 scattered and visibility is greater than 10 miles. It is a beautiful day to be boring some holes in the sky. Then, it happens. There are wisps of dark smoke coming from under the instrument panel. You also notice a distinctive odor of something burning.

You remind yourself that you need to try to remain calm. What do you do next, and where is the pilot’s operating handbook (POH)? You need to find the “emergency procedures” section now!

Fortunately, fire in the cockpit and other in-flight emergencies are not common in GA aircraft. Unfortunately, if an emergency does occur, many GA pilots are not well-prepared to deal with it.

I will be the first to admit that I am not as well prepared as I should be. Yes, I am current, and I try to fly regularly to be proficient and confident in my flying skills. But, like many other GA pilots, I often don’t think about what I can do specifically to become a better pilot.

I am not talking about obtaining additional ratings (although that would certainly make me a better pilot), or about spending additional time with a Certified Flight Instructor (CFI) for a flight review or extra training (although either could enhance my skills).

I am suggesting, as GA pilots, that we should never be satisfied with the status quo. We can choose to become better pilots, and we should be willing to work, on our own, on aspects of our flying that can assist us to meet our personal goals and make our flying safer.

Fire in the cockpit requires an immediate, practiced response. As PIC, you may not have time to rummage through side or backseat pockets for the POH and then page through it to locate the “emergencies” section. Every second counts. Aviation experts advise that good pilots commit certain emergency procedures to memory and practice those procedures on a regular basis. By committing the four or five critical steps to memory regarding emergency scenarios and using a “flow check” to walk through the steps on your airplane’s panel, you will gain valuable time – time that may be necessary to save the lives of everyone on board.

A large part of what we can do on our own to become better GA pilots involves preparation. Here are three things the experts say can help us to better prepare for circumstances we may encounter during a flight:

First: Commit certain emergency procedures to memory. The Information Manual for the 1981 Cessna Skyhawk (Model 172P) lists six different general categories of checklists for emergencies: Engine Failures, Forced Landings, Fires, Icing, Landing with a Flat Main Tire, and Electrical Power Supply System Malfunctions. Engine failure, fire, and icing are the most serious matters to deal with in-flight and likely require the most immediate responses.

Engine failure checklists should be familiar to all GA pilots, as CFIs have been pulling power back on us and announcing “engine failure” from the time we were all student pilots. There are several key steps that should be committed to memory, including lowering the nose of the aircraft to attain best glide airspeed, locating a suitable landing site, and commencing a list of trouble-shooting actions including checking carburetor heat, fuel selector valve, mixture, ignition/mags, and primer.

Most emergency checklists involve some combination of items relevant to the specific emergency. They are short lists, and with a little practice, you should be able to commit them to memory. Some pilots may prefer to use Mnemonics as a reminder. For example, an easy one to remember for engine failure is “A, B, C, D” – Airspeed, Best Place to Land, Checklist, and Dialogue. Also, by using a flow check of the relevant levers, switches, and controls, you can more easily visualize the sequence and location of each item to be checked in an emergency.

As pilots, we should be willing to spend sufficient time on the ground with our aircraft POH’s emergencies checklists. With a personal commitment to learning emergency procedures/checklists on the ground, and with a willingness to spend some time on memorization and periodic refreshers, we will be in a better position to respond quickly, and correctly, when confronted with an emergency in the air.

Second: Practice flying when not in the airplane. I have a friend who is a retired U.S. Air Force pilot. He fondly remembers his training days years ago when he frequently used “chair flying” to hone his flying skills. At the end of the day, he would sit in a kitchen chair, with one hand on an imaginary stick, the other on an invisible throttle, and both feet located on non-existent rudder pedals.

He wisely used his free time when he was not in an actual cockpit to practice the sequence of steps necessary for each flight procedure or maneuver. Elite athletes understand and are familiar with the concept of “muscle memory” (i.e. the repetitive practice of a series of motions that your brain and muscles come to know so well they become “automatic”). Once that level of muscle memory is achieved, it is no longer necessary to consciously think about coordinating your hands and feet, or where to reach for a desired switch or lever. Your brain thinks – and your body reacts.

GA pilots can also benefit from chair flying. It is particularly valuable when you want to practice something that requires a series of prescribed steps, such as flying a traffic pattern, practicing emergency procedures, or rehearsing steps in flight maneuvers like stalls, steep turns, or chandelles.

Today’s GA pilots, because of technology, also have a distinct advantage over chair flyers. A desktop flight simulator, such as X-Plane or Microsoft Flight Simulator, with a suitable yoke or stick and rudder pedals, offers an enhanced, modern version of chair flying with a remarkable level of realism not available with a simple chair in your kitchen.

Many GA pilots fly 50 hours a year or less. Taking the time to practice when you don’t have access to a real airplane by chair flying or using a flight simulator can pay valuable dividends. It allows you to practice at little or no cost, on your schedule, and provides a level of enhanced confidence in your performance when you climb into a real cockpit.

Third: Work Through Risk Management Scenarios. One of the biggest risks to GA pilots is weather. Often, National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) reports conclude that a VFR pilot made the decision to initiate or continue a flight into known adverse weather conditions, resulting in spatial disorientation, loss of control, and subsequent in-flight breakup. Why does that happen?

One likely reason is that GA pilots (as a group), generally, have not developed a high level of aeronautical decision making (ADM) skills. Many GA pilots have not received much formal training to acquire and practice these skills. Today, that is changing and there is much more emphasis by the FAA, CFIs and designated pilot examiners (DPEs) on ADM, as it is required to be taught as part of the private pilot training curriculum.

GA pilots can and should develop risk assessment skills. Good judgment and experience are assets to us in our flying, but they sometimes are not enough. Pilots also need processes that are objective, repeatable, and reliable.

Personal minimums for VFR or IFR are a very good start. When I flew out of the Fond du Lac, Wisconsin airport (KFLD), an emergency medical helicopter was based on the field. I asked the pilots how they made a “go/no-go” decision. For them, it was easy. Even though the pilots and helicopter were IFR certified and current, their Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) required VFR-only flights. That eliminated any subjective desire the pilots may have had to undertake an otherwise risky mission.

Hazard and risk analysis is also a good tool. A “hazard” is defined as “a real or perceived condition, event, or circumstance a pilot encounters.” It could be a thunderstorm on the horizon… it could be forecast icing… or it could be a leg of a trip over open water at night when you are fatigued. Once recognized, the pilot then assesses the hazard and assigns a value to its level of risk based on the pilot’s knowledge, ratings, currency/proficiency, and experience. A risk, based on the likelihood of the hazard occurring, can be identified as “probable, occasional, remote, or improbable.” A VFR-only pilot launching into instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), or continuing a flight into IMC, needs to recognize the risk of spatial disorientation and loss of control as probable and must make the decision to not depart or, if in the air, to turn back.

As GA pilots, most of us chose to fly because we love being in the air. I think many of us also enjoy the challenge of flying an airplane well, and even though we don’t get paid, the personal satisfaction of being good at it. We should also understand, and accept, our responsibility to continue to get better (©Dean Zakos 2019).

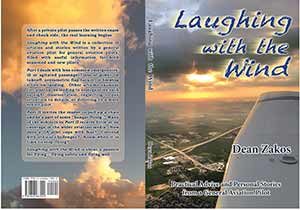

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dean Zakos (Private Pilot ASEL, Instrument) of Madison, Wisconsin, is the author of “Laughing with the Wind, Practical Advice and Personal Stories from a General Aviation Pilot.” The book is available from Square Peg Bookshop (http://squarepegbookshop.com/), Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Chapters Indigo (Canada) and other retailers. Comments and personal flight experiences are welcomed: drzakos@sbcglobal.net

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dean Zakos (Private Pilot ASEL, Instrument) of Madison, Wisconsin, is the author of “Laughing with the Wind, Practical Advice and Personal Stories from a General Aviation Pilot.” The book is available from Square Peg Bookshop (http://squarepegbookshop.com/), Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Chapters Indigo (Canada) and other retailers. Comments and personal flight experiences are welcomed: drzakos@sbcglobal.net

DISCLAIMER: The information contained in this column is the expressed opinion of the author only, and readers are advised to seek the advice of their personal flight instructor and others, and refer to their aircraft’s Pilot’s Operating Handbook, Federal Aviation Regulations, and the FAA Aeronautical Information Manual before attempting any procedures or suggestions discussed herein.