by Rick Braunig

Published in Midwest Flyer Magazine August/September online issue

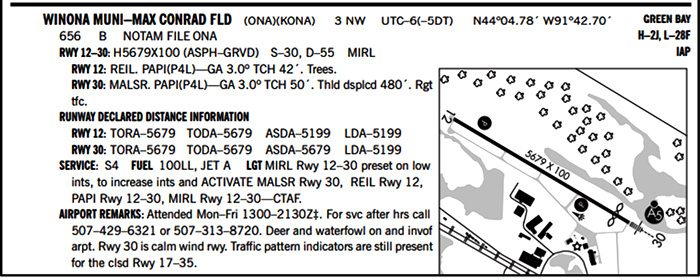

There aren’t a lot of runways with displaced thresholds in Minnesota, but they are common enough that pilots should be familiar with them. When a runway has a displaced threshold, the landing distance available (LDA) is shorter than the runway length. The threshold to Runway 30 at Winona Municipal-Max Conrad Field (KONA) is displaced by 480 feet, meaning that aircraft are not supposed to land before that point on the runway. When landing on Runway 30, the pilot does not have the full 5,679 feet to land on, but rather, only 5,199 feet. This information is shown on the top line of approach plates or in the Declared Distance information in the Chart Supplement (Green Book).

Displaced thresholds are usually added to clear obstructions in the approach. There are requirements for approach slopes that are based upon the type of approach to the runway. In this case when we say type, we are talking about whether the approach has to be visual or if there is an instrument approach to the runway end. If an object penetrates the required slope, the FAA allows the use of a displaced threshold to clear the slope. Displaced thresholds are marked and lighted so the pilot can identify them during both day and night operations.

Of course, runways can be used in two directions, so it stands to reason that an approach obstruction to Runway 30 would be a departure obstruction to Runway 12. Departures are normally made with maximum thrust and the climb is normally at best angle of climb (Vx) until the objects are cleared. While an aircraft can legally use the entire runway for takeoff, that does not ensure that they will be able to clear the obstructions on climb out. If you notice on climb out that you are not going to clear the obstruction, the only choice left is to try to turn to avoid it. A good rule of thumb is to always plan to lift off by any displaced threshold on the reciprocal runway, giving you a better chance of clearing the obstructions. Unfortunately, the displaced threshold can be hard to see at night because the displaced threshold is not lighted for aircraft going the opposite direction.

It is interesting to note that the LDA for Runway 12 at Winona is also 5,199 feet. There is no displaced threshold to Runway 12, so why can’t all 5,679 feet be used for landing? The answer is that the usable runway has been shortened by the distance required for the Runway Safety Area (RSA). The RSA is a defined surface surrounding the runway, prepared or suitable, for reducing the risk of damage to airplanes in the event of an undershoot, overshoot, or excursion from the runway. The RSA is also meant to support aircraft rescue and firefighting equipment if needed for an aircraft crash and to support snow removal equipment to help the airport keep the RSA usable year-round. At Winona, both the displaced threshold and the shortened landing distance for Runway 12, are because of the RSA requirement and not because of obstructions.

At Jackson Municipal Airport (KMJQ), the planned Runway 13/31 is 4,142 feet long, but the usable length is really 3,591 feet. In this case, declared distances are being used to clear the Runway Protection Zone (RPZ). The RPZ is an area at ground level prior to the threshold or beyond the runway end to enhance the safety and protection of people and property on the ground. The RPZ extends out beyond the RSA covering a larger area. The RPZ is causing a displaced threshold on both ends and a shortened LDA, but it is also shortening the Takeoff Runway Available (TORA), which is normally the length of the runway. The only operation that can use more than 3,600 feet in either direction would be the accelerate-stop (ASDA) or rejected takeoff. Pilots are supposed to calculate their takeoff distances and on departure, liftoff prior to the TORA distance, but there are no markings indicating the location of the shortened TORA, making it invisible to the pilot.

If you haven’t heard about this before, you are not alone. The FAA changed their position several years ago on RSA and RPZ and started requiring full compliance at commercial service airports. Those requirements are now being required at all airports that accept federal funds when the airport has a runway project.

Many of the smaller airports in Minnesota do not currently meet RSA or RPZ standards. I believe Winona was the first Minnesota airport to employ declared distances beyond using a displaced threshold to clear obstructions, but they will not be the last. The Minneapolis Crystal Airport is using them on Runway 14/32, and as discussed, there are plans to incorporate them at Jackson, Minnesota when that runway is rebuilt. Others are also in the planning process.

The RPZ and RSA are surfaces defined in the Airport Design Advisory Circular. Though the name implies that compliance is advisory, airports that take federal funds agree to abide by the advisory circulars as part of grant assurances. Airports that don’t take federal funds are not obligated to clear these surfaces and the Minnesota licensing requirements do not include RSAs or RPZs, so airports that only get state or local funding do not have to clear these surfaces.

The purpose of both the RSA and the RPZ is to improve the safety of the airport by providing room for crashes that leave the runway. When building a new airport, RSA and RPZ requirements should be taken into account in site selection, so that the entire runway is usable. Existing airports have limitations.

For both Crystal and Jackson, they are limited by the development off the ends of the runways. From the pilot’s view, we would like to see the airport buy more property so the runways can be longer and the RPZ and RSA are not impacted using the full length. Unfortunately, that property cannot be easily acquired. At Jackson, without using declared distances, the new runway on the available footprint would be 3,060 feet. As noted, the current runway is 3,591 feet. The airport could not accommodate the current aircraft mix if reduced to 3,060 feet, so declared distances are planned. Other airports will encounter similar issues when applying the RSA and RPZ requirements, and in some cases, the result will be a shortened runway even with declared distances. As a pilot, I would prefer more runway to safely complete the takeoff or landing so that the crash these surfaces address is less likely to occur.

The guidance to pilots on declared distances is confusing. In the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM), it states that the distances must be calculated based on the information in the aircraft flight manual or operating handbook, and those numbers must be less than the declared distances for the pilot to accept the runway. In the Airport Design Advisory Circular, it states that declared distances are for turbine aircraft. In any case, knowing the declared distances and applying them to your operations can only increase your safety.

Going forward, pilots should be aware that the total runway length might not be available for takeoff or landing and the chart supplement is the place to find that information. The FAA publishes the chart supplements online at: https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/flight_info/aeronav/digital_products/dafd/

EDITOR’S NOTE: Rick Braunig has a degree in Aerospace Engineering and Mechanics from the University of Minnesota. Upon graduation he accepted a commission in the United States Navy and flew both airplanes and helicopters on active duty for 10 years. Rick continued in the Navy Reserves for another 17 years working in aircraft survivability and battle damage assessment. He retired from the service in 2007 at the rank of Captain.

In 1990, Rick took a position with the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) Office of Aeronautics, where he flew a Bonanza and King Air, compiling more than 7,000 hours over his career. He was a part of the FAA safety team that presented pilot safety seminars throughout Minnesota for a number of years starting in the late ‘90s.

Prior to his retirement from MnDOT in 2021, Rick was the manager of the Aviation Safety and Enforcement Section. In this role, he trained and supervised the team responsible for the inspection and licensing of airports, heliports and seaplane bases in the state.

Rick lives with his wife, Kelly, in Woodbury, Minnesota.

DISCLAIMER: The information contained in this column is the expressed opinion of the author only, and readers are advised to seek the advice of their personal flight instructor, mechanic, attorney and others, and refer to the Federal Aviation Regulations, FAA Aeronautical Information Manual and instructional materials before attempting any procedures or following any advice discussed herein.