“I always knew I would get here. What I did not know is how quickly…”

by Richard Morey

© Copyright 2024. All rights reserved!

Published in Midwest Flyer Magazine June/July 2024 Digital Issue

I was born into a flying family, which has been both a blessing and a curse. The curse, if one could call it that, is that flying, at least initially, was nothing special. I did not experience the infatuation with aviation as most students do. To me and my sister, flying was much like getting in the family station wagon and heading out on vacation. One of my good friends commented recently that the most relaxed he ever sees me is when I am flying in the right seat, giving instruction.

My father is, and my grandfather was a pilot. The family business was, and is a flight school in Middleton, Wisconsin (C29). I grew up at the airport. The blessings of growing up in aviation are that I see flying for what it is. When I was younger, I asked my grandfather, Howard Morey, what his favorite aircraft was. Instead of some exotic high-performance aircraft, grampa’s answer was a Cessna 172.

“The 172 is an airplane everyone can handle, and one a flight school can afford and make money with.”

He went on to tell me that to run a flight school, you could not buy aircraft because you wanted to fly them… Rather, you must evaluate what is best for the business. I took those words to heart.

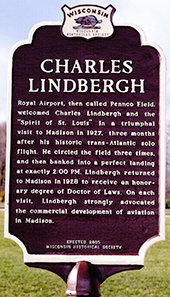

Howard Morey started flying in 1923 at the Eddy Heath School in Chicago. After he graduated, he worked for

Mr. Heath for a time, until he and a fellow student purchased a Curtis JN4-D, a surplus World War I training aircraft known affectionately as a “Jenny.” They headed north planning on spending the winter in Birchwood, Wisconsin with grampa’s family. They stopped in Monona, Wisconsin to spend the night with a cousin. That evening it snowed a lot. The snow made it impossible to continue their flight to Birchwood. Instead, they made arrangements to store the Jenny in a barn and continued their trip via train. When he returned in the spring, a neighboring farm owner convinced him to establish an airport and make the Madison, Wisconsin area his home base. Grampa took his advice and started a flight school in the Madison area in 1925. In 1938, he moved operations to the brand-new Madison Airport (now Dane County Regional Airport) and became its first manager.

In 1941, shortly after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II, the Army Air Corps took over Madison Airport, and grandpa had two weeks to move operations, first to Lone Rock, then in the spring of 1942, he started operations in Middleton where Morey Airplane Company has been ever since.

Howard’s son and my father, Field Morey, took over as manager in 1968 when I was 10 years old. I started cutting grass and cleaning aircraft in 1972, working myself into the exalted position of a “line guy” shortly thereafter. I learned to drive a manual transmission Clark Tug tractor and 1949 Dodge fuel truck. You did not shift the truck; you simply started it in the gear you wanted. There really was no reason to shift out of first. I felt the same way about the tug, earning myself the nickname “One Speed.” That suited me just fine. Slow and steady tends not to bend aluminum.

My flight training started in February 1974. At least that was when I started logging my time. I am not sure how much unlogged time I had at that point. I soloed on March 24, 1974, on my 16th birthday. Thus, the 50 years of flying. I soloed with 7 hours and 25 minutes of instruction, most of which was doing crosswind landings. This was good experience, as I soloed in a strong crosswind.

My father was my instructor through solo. Back before the FAA wisely expanded what is required to solo, it was common for students to solo in under 10 hours. Those of you who read my article on crosswind landings (https://midwestflyer.com/?p=15243), know the story. The short version is that I made what I considered horrible landings while riding with my father that day. Much to my surprise dad decided to send me up by myself to solo, despite my poor performance.

The three landings that followed were considerably better. Despite my apprehension, by father knew I had the skills and ability, and faith in that I would rise to the level of my training. Fifty years later, I can still remember the pride I felt after soloing, and the focus I felt once dad left the airplane.

Fifty years is a long time, especially regarding aviation. I have been reminiscing about how flying has changed from my first solo until today. My initial impression is that flying itself has not changed a great deal. Landing, taking off, and maneuvers have not changed. The Cessna 150 I soloed in back in 1974 is not much different than the Cessna 152s we use today. Same with the Cessna 172. Legacy aircraft when properly maintained do not seem to wear out. What has changed is the avionics, and the prevalence of computer use in aviation.

For example, when I started flying, pilotage and dead reckoning were the most common way to fly cross country. Ground based navigation was used primarily for instrument flights, and occasionally for longer visual flights. Most aircraft used for private pilot training had one nav-com, and possibly a transponder. Sectional charts or world aeronautic charts (WACs) were always used for cross-country flights, with flight logs filled out. Check points, and estimated times to these points, were on the flight log. A trusty E6B was at hand to recalculate ground speed if necessary.

Pilotage, for those who are unfamiliar, is the art and science of knowing where you are by simply looking out the window at the terrain and correlating that with the sectional chart. The old joke, “I fly IFR” (I follow Roads, Railroads and Rivers is based on pilotage and the even earlier days of aviation).

When my grandfather flew Wisconsin’s governor to New York for an aviation conference back in the ‘30s, he used railroad maps. “They were the most accurate maps available at the time,” said Howard Morey.

The rule when flying cross country via pilotage is, “verify your checkpoints.” Confirmation bias was not a term commonly used back in the 1970s, but the concept of wanting something to influence a person’s decision-making was well known.

Mark Finley, one of the many excellent flight instructors I have had the pleasure to fly with, gave me very good advice when it comes to identifying checkpoints. “Always look for three things about the checkpoint before deciding it is what you want it to be,” or “when in doubt, read the water tower.” My long cross country for my private pilot certificate was flown in a Cessna 150 Aerobat with no gyro instruments and a very untrustworthy VOR. Understanding compass error and pilotage skill was essential for that flight. I made it from Middleton to La Crosse, Wisconsin and then to Dubuque, Iowa with no issues. In 1979, as a private pilot, I flew a brand new C172 with no radios installed, back to Wisconsin from the Cessna factory in Wichita, Kansas. I navigated via pilotage and dead reckoning. This aircraft did have gyros though. We still own that 45-year-old C172, now with radios. With over 16,000 airframe hours, it is one of the more popular aircraft in our training fleet! I wonder how many of today’s pilots would be comfortable flying cross country in an aircraft without radios using only sectional charts for navigation.

Weather briefings were via telephone, not computer. An overview was available on the evening televised weather report. My memory suggests that the forecasts were every bit as accurate then as they are now. My meteorologist friends would disagree with me on this.

In my 50 years of flying, I have logged over 20,800 hours of flight time, of which over 15,000 hours have been as a flight instructor. I have spent 2.37 years above planet Earth! My father has over “Four years above the earth,” as attested to in his book of the same title.

Some of the highlights of the last 50 years include:

• Attending Black Hawk Technical Institute in Janesville, Wisconsin from 1979 – 1981, obtaining airframe and powerplant certificates, and earning inspection authorization in 1984.

• Being part of the Morey glider program as a tow pilot and obtaining a commercial glider rating. I hold a flight instructor-instrument certificate for both single-engine land and multi-engine land, and an airline transport pilot (ATP) certificate.

• I am a Gold Seal flight instructor, and an EAA Young Eagles flight leader.

• In 2020, I graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh (UWO) with a Bachelor of Science Degree in Aviation Management. (My mother always hoped I would eventually earn a bachelor’s degree.) UWO has a wonderful online program for those like me who have a two-year technical education, but not a four-year degree. Taking online classes in itself was an education in technology. It was interesting being the oldest student in my classes. My perspective was appreciated by my younger classmates. For my part, my love of learning made the classwork fascinating.

My father sold Morey Airport to the City of Middleton in the late 1990s. The airport was “state of the art” in 1942, but needed improvements that the family could not afford. Now as a municipal airport, federal and state funding is available.

The current airport is a result of the city’s foresight in recognizing its value to the community. The improvement project was completed in 2004.

In March of 2003, I took over as owner of Morey Airplane Company, and became the airport manager for the City of Middleton. As airport manager, I was both eager and apprehensive. Much like my first solo flight, I knew I had the training and skills, and my father had faith in my abilities. Having to run the business largely on my own was a daunting task. After 21 years, I am struck at how similar my taking over the business is to my first solo.

I honestly do not know how many student pilots I have recommended for their check-rides. I am blessed to have taught so many students, and humbled by their accomplishments and the friendships that grew out of their training. I do not know how many different models of aircraft I have flown. It is safe to say that if it is a single piston-engine Cessna with tricycle gear, I have flown it. I have some C195 time with my father. I have flown Cirrus, Diamond, Beechcraft, Piper, Husky, Citabria, Taylorcraft, and Luscombe aircraft and many others, and have enjoyed flying all of them, some of course more than others. Most recently, I went to school to get checked out in a Piper Malibu Mirage, a very capable, pressurized single-engine aircraft.

I do not really have one favorite aircraft. I do believe that it is hard to beat a Cessna 152 as a trainer, a Cessna 172 as a rental aircraft, a Cessna 182 as a family aircraft, and a Cessna 310R or 340A, as a light twin charter aircraft.

The most interesting flying I have done has been as a flight instructor on my father’s West Coast Adventures IFR training trips, flying a Cessna 182RG turbo. EAA Young Eagles and Willa Brown flights have been the most satisfying because I get to introduce aviation to young people. My work with Willa Brown is especially satisfying in that the focus is in introducing aviation to young people of underrepresented populations, women, and people of color for the most part. My oddest flight was as a passenger in a Goodyear blimp, which was moored at our airport sometime in the 1980s. Probably the most interesting aircraft I have flown is a Ford Tri-Motor during EAA AirVenture. My most dangerous flight involved un-forecast severe icing while giving instrument instruction. The details of which are worth mentioning.

We had gone missed after an ADF approach into Dane County Regional Airport (KMSN), Madison, Wisconsin. (Side note, I DO NOT miss ADF approaches.) We picked up some ice on the approach and a lot more ice on climb out. That was the first, and hopefully the last time I will have to declare an emergency.

We were then vectored for an ILS approach. I remember thinking that we only had one chance at this approach and that a go-around was not an option. With this in mind, I resolved to make sure we made this approach, even if it required us to go below minimums. In an emergency, you may deviate from the regulations to the extent necessary. Oddly, I was not scared at the time and exhibited what the FAA calls “appropriate response to stress.” The extreme focus on flying excludes emotions.

We were picking up clear ice; that is, water striking the leading edge of the airfoils, running back in liquid form, then freezing. This results in what some pilots call “horns” of ice. These horns act as spoilers and kill lift.

A normal ILS approach in a C182RG is flown with 15 inches of manifold pressure, 10 degrees of flaps and gear down. This results in about a 500 feet per minute descent and 90 knots of airspeed. The additional drag we had from the ice required nearly full power with flaps and gear up to get the same performance. In other words, the drag of the ice was a great deal more than having gear and 10 degrees of flaps down! We broke out about 300 feet above the runway with the main struts vibrating. It is not unusual to get structural harmonics when iced up. This vibration sounds like a low-pitched hum.

Luck played a part here as once we were clear of the clouds and in the above freezing surface air, all the ice broke free… first the right wing, then the left. The ice leaving the aircraft made a deep base note or boom. This loss of ice allowed for a normal landing.

Once safely on the ground with my student, I found myself alone. That is when the shaking started. That is when the full weight of what had just happened came to rest on my shoulders. I had done what I needed to do for my student and myself to survive. Likely, there was very little margin for error in this. Both luck and skill came to play in the successful outcome of the flight.

My most meaningful flights are the ones with my father and my grandfather. My father because of all he taught me. My grandfather because his last flight with me was the last time he flew an aircraft.

I have flown light aircraft to Alaska, St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands, and pretty much everywhere in between. In my 50-plus years of flying, I have been blessed to fly with some amazing instructors, students, and pilots. I do believe that every one of them taught me something of value.

I have yet to pilot anything that burns Jet A, or fly in a balloon, both of which I would enjoy doing. When Cuba opens up again to general aviation, I would love to fly there. Revisiting Alaska and the Idaho back-country would be worthwhile. A seaplane rating may be in my future. Getting some stick time in the models of aircraft grampa flew is a goal. I doubt I will be able to fly a “Jenny,” but a Waco taper-wing is certainly possible. Mostly I look forward to another few decades of teaching people to fly. Dad is 85 now and still flying and instructing, so I expect another 20 years at a minimum for myself.

My first 50 years have been an amazing experience. At 66, I am in the third quarter of my life. I plan on continuing this adventure for as long as I am allowed.

What does it take to have a long career as a pilot? I would suggest that it is the same as having a long life. Take care of your health. This means staying fit and trim. Eat well, sleep well, enjoy your friends and family. We as pilots are incredibly fortunate in what we experience and the beauty we witness. Never stop learning and never lose your sense of curiosity. Keep your sense of wonder about you! We thrive when challenged. Do not fall into complacency but continue to challenge yourself both in your flying and your life. Make a difference; share aviation with those around you.

If my last 50 years has taught me anything, it is the value of laughter. Life is too short and too important to be taken seriously!

Live life with urgency! Tomorrow is not guaranteed, so do your best not to put off the important things in your life.

Finally, the best advice I can give any pilot for having a long flying career is to invest in yourself by taking regular flight instruction. I have spent the last 50 years learning, studying, and practicing. As a charter pilot, I have flight checks with the FAA every six months. That, and learning to fly new aircraft with new avionics have kept me sharp.

Work on your weak points, be it crosswind landings, learning the new-to-you GPS, or staying instrument current. Regular instruction is the only way to maintain your skill level and the cheapest life insurance you can buy.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Richard Morey was born into an aviation family. He is the third generation to operate the family FBO and flight school, Morey Airplane Company at Middleton Municipal Airport – Morey Field (C29). Among Richard’s diverse roles include charter pilot, flight instructor, and airport manager. He holds an ATP, CFII, MEII, and is an Airframe and Powerplant Mechanic (A&P) with Inspection Authorization (IA). Richard has been an active flight instructor since 1991 with over 15,000 hours instructing, and more than 20,000 hours total time. Of his many roles, flight instruction is by far his favorite! Comments are welcomed via email at

Rich@moreyairport.com or by telephone at 608-836-1711.

(www.MoreyAirport.com).

DISCLAIMER: The information contained in this column is the expressed opinion of the author only. Readers are advised to seek the advice of their personal flight instructor, aircraft technician, and others, and refer to the Federal Aviation Regulations, FAA Aeronautical Information Manual, and instructional materials concerning any procedures discussed herein.