by Hal Davis

WisDOT Bureau of Aeronautics

As I write this, I have yet to see my first snowflake of the forthcoming winter season, but that’s likely to change any day now. The winter season means different things to different people in the aviation world. To pilots, it usually means smoother and clearer skies, better engine performance, and brushing up on your NOTAM contractions. To the men and women who keep our airports open for business, the winter season means it’s time to dust off and fuel up the snow removal equipment. Just like on the public roadways – removing snow at some of the largest and busiest airports can involve a significant amount of planning, specialized clearing methods, and a fleet of heavy-duty equipment to do the job effectively.

While all airport operators want to keep their airports open for business at all times, some simply don’t have the staff or the equipment to keep up with an often unrelenting Mother Nature. Therefore, it’s important that both airports and pilots are aware of what is required when it comes to snow removal.

For commercial service airports, the FAA requires “prompt” removal of snow. For general aviation airports, the FAA does not impose any specific responsibility on the airport to remove snow or ice other than providing a safe and usable facility. If a winter storm renders parts of the airport unsafe, the airport is only obligated to promptly issue the necessary NOTAM, and close all affected parts of the airport until the unsafe conditions are remedied.

The airport should then correct unsafe conditions within a “reasonable” amount of time. Naturally, you may ask, “What is reasonable?”

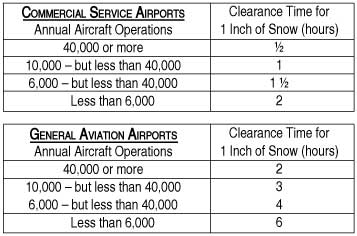

Ultimately, determining what is reasonable will depend on the characteristics of the snowstorm, the capabilities of the airport, and the needs of the airport users. However, in FAA Advisory Circular 150/5200-30C, Airport Winter Safety and Operations, snow clearing times are established by airport type and number of annual aircraft operations for the purpose of determining necessary snow removal equipment. The following tables should not be interpreted as a requirement for clearing times, rather general goals under ideal conditions.

In the heat of the battle, it’s nearly impossible for any airport to keep all runways, taxiways, and aprons in a pristine condition. This makes surface condition reporting all that more critical. Pilots should know the limitations of their aircraft and their own piloting skills whenever operating with snow, slush, or ice present. As little as a half-inch of wet snow or slush can significantly decrease deceleration rates and increase the potential for hydroplaning (see FAA Advisory Circular 91-6A, Water, Slush, and Snow on the Runway). Airport operators must stay alert for changing surface conditions and report them via NOTAM. On the other hand, pilots must take the time to read and understand exactly what conditions are being reported.

Reporting airfield conditions in a timely manner is a requirement for all commercial service airports.

This past August, the FAA made some changes to field condition (FICON) NOTAMs. The changes are meant to bring the U.S. NOTAM System closer to ICAO compliance and make them easier for airmen to read. For more information on the changes, see FAA Order JO 7930.2N.

When reporting field conditions, a FICON NOTAM will always follow the same sequence: surface affected, coverage, depth of contaminant, and condition. For example: runway 36, patchy, thin, snow (RWY 36 PTCHY THN SN). The term “patchy” means 25 percent or less of the surface is covered. Depth of snow is expressed in terms of thin, 1/8 inch, 1/4 inch, 1/2 inch, 3/4 inch and 1 inch. When one inch is reached, additional depths are expressed in multiples of one inch, and the use of fractions is discontinued. Airports may report a variety of surface conditions. Check out FAA Order JO 7930.2N for more information on NOTAM formatting and possible contaminants.

Reporting braking action is another crucial element to field condition reporting. Most pilots are familiar with the terms “good,” “fair,” “poor,” and “nil.” When a pilot provides a braking action report using these terms, or any combination thereof, the most critical term will always be used when issuing a corresponding NOTAM. For example, a “fair to poor” report would result in a NOTAM indicating poor breaking action or BRAP. Any braking action report of “nil” or two consecutive reports of “poor” requires the runway to be closed until the contaminant is removed or the airport operator is satisfied that the condition no longer exists.

Commercial service airports will also measure and report runway friction through the use of a decelerometer. The Greek letter MU (pronounced “myew”) is used to designate friction values for a surface. MU values range from 0 to 100, where zero is the lowest friction value and 100 is the maximum friction value attainable. The lower the MU value, the less effective braking performance becomes and the more difficult directional control becomes. However, aircraft-braking performance only begins to deteriorate at a MU value of 40 or less. Therefore, any MU value over 40 is not reported.

MU values are reported in runway thirds. For example, a report of 40/30/20 means that no affect on braking performance is anticipated in the first third. However, the MU value in the middle third indicates deteriorating performance, while value for the final third indicates braking performance is significantly decreased. Pilots should use MU information along with other knowledge including aircraft performance characteristics, type, weight, previous experience, wind conditions, and aircraft tire type to determine if a runway is suitable for their unique needs. It should also be noted that no correlation has been established between MU values and the descriptive terms “good,” “fair,” “poor,” and “nil” used in braking action reports.

On the public roadways, road salt is used to melt ice and snow to increase friction values. However, did you know that the FAA prohibits the use of salt on airports? Instead, non-corrosive, environmentally-friendly alternative chemicals are used in conjunction with sand.

The winter season presents unique challenges to both pilots and airport operators. As we enter this coming season, I encourage all airports and airport users to start a dialogue focusing on safety and expectations for the season ahead. For more information on winter operations at airports, please see FAA Advisory Circular 150/5200-30C, Airport Winter Safety and Operations. This AC is mandatory for all commercial service airports and advisory for all other airports.