by Levi Eastlick

WisDOT Bureau of Aeronautics

Published online Midwest Flyer Magazine – February/March 2021

At a time when shaking hands or seeing a stranger’s smile might be as rare as an airworthy SBD Dauntless, there is no better escape from the strange than to fire up the flat engine and get some fresh air under our feet. Flying provides a sense of freedom and peacefulness, not to mention some incredible views that only other aviators and our feathered friends (or foes, depending) can experience. The stunning perspective from above can get us in trouble though if we aren’t careful. Federal Aviation Regulation (FAR) §91.119 establishes the “Minimum Safe Altitudes” that we are permitted to fly. But just because we can, doesn’t mean we necessarily should.

At a time when shaking hands or seeing a stranger’s smile might be as rare as an airworthy SBD Dauntless, there is no better escape from the strange than to fire up the flat engine and get some fresh air under our feet. Flying provides a sense of freedom and peacefulness, not to mention some incredible views that only other aviators and our feathered friends (or foes, depending) can experience. The stunning perspective from above can get us in trouble though if we aren’t careful. Federal Aviation Regulation (FAR) §91.119 establishes the “Minimum Safe Altitudes” that we are permitted to fly. But just because we can, doesn’t mean we necessarily should.

Before we go any further, let’s look at what’s in the regulation itself. It may come in handy during your next flight review or WINGS activity!

§91.119 Minimum safe altitudes: General.

Except when necessary for takeoff or landing, no person may operate an aircraft below the following altitudes:

(a) Anywhere. An altitude allowing, if a power unit fails, an emergency landing without undue hazard to persons or property on the surface.

(b) Over congested areas. Over any congested area of a city, town, or settlement, or over any open air assembly of persons, an altitude of 1,000 feet above the highest obstacle within a horizontal radius of 2,000 feet of the aircraft.

(c) Over other than congested areas. An altitude of 500 feet above the surface, except over open water or sparsely populated areas. In those cases, the aircraft may not be operated closer than 500 feet to any person, vessel, vehicle, or structure.

Digging a little deeper into this regulation, it’s important to first note it excludes takeoff and landing. Next, it outlines three general situations. The first, and arguably most important requirement, applies anywhere and everywhere. At all times, an aircraft must be flown at a high enough altitude that if the aircraft loses power, it can glide to make an emergency landing where only the aircraft has the potential of being damaged.

The other two situations identified are over congested areas and over other than congested areas, including open water and sparsely populated areas. How the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) defines these areas depends on a variety of factors. Feel free to look at FAA legal interpretation letters and past court cases if you’re curious about what exactly it depends on. As you fly, the key question to ask here is: “How many people and structures are below me?” Then fly at the appropriate altitude. Over open water or sparsely populated areas, minimum altitude no longer applies, but a minimum distance from people and things does. Keep in mind, unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) are legally allowed to operate 400 feet above the ground and are a relatively new risk to consider should you choose to fly low.

Situational awareness is critical for safety of flight and is tremendously pertinent to minimum safe altitude regulations. Flying low requires additional attentiveness to identify all obstacles, buildings, people and vehicles in order to determine the appropriate flight altitude and distance, all while remembering to preserve the ability to glide to a safe emergency landing area.

Exceptions

Of course, like most regulations, there are exceptions to the rule. Besides during takeoff or landing, helicopters, powered parachutes and weight shift control aircraft have slightly different legal minimums than conventional aircraft. Agricultural aircraft operating under FAR Part 137 and military aircraft may be allowed to fly lower as well. Finally, pilots may also receive a waiver from all or specific parts of this rule if they’re willing to complete the paperwork and provide adequate justification.

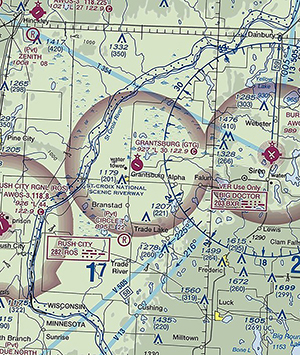

Additionally, there are some locations where we legally should fly higher than the minimums prescribed in §91.119. Altitude restrictions exist for Temporary Flight Restrictions (TFRs), especially stadiums and powerplants, as well as prohibited areas like  the Boundary Waters Canoe Wilderness Area in northern Minnesota. The airspace above national parks, wildlife areas and forests is also protected to some extent. These areas can be identified on a sectional chart by name and an associated thin blue line with adjacent blue dots. Here’s what it says on the sectional.

the Boundary Waters Canoe Wilderness Area in northern Minnesota. The airspace above national parks, wildlife areas and forests is also protected to some extent. These areas can be identified on a sectional chart by name and an associated thin blue line with adjacent blue dots. Here’s what it says on the sectional.

Although it says requested, not required, these areas commonly have heavy concentrations of birds, so higher is certainly safer. Furthermore, if we want to continue to enjoy these places from above, we should strive to be good citizens and reduce our impact by staying both high and quiet. For more information about these noise sensitive areas, check out FAA Advisory Circular 91−36D.

Of course, there are a lot of interesting places that are not found specifically on a sectional chart or listed in the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM). Local and state parks, tourist attractions and national historic landmarks certainly draw airborne visitors. While there are no additional rules we need to remember when flying over these places, always try to enjoy the view as safely and quietly as possible.

Of course, there are a lot of interesting places that are not found specifically on a sectional chart or listed in the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM). Local and state parks, tourist attractions and national historic landmarks certainly draw airborne visitors. While there are no additional rules we need to remember when flying over these places, always try to enjoy the view as safely and quietly as possible.

Enforcement

So, what happens if someone breaks the rules? If an FAA investigation determines that a pilot was flying too low or too close to somebody or something, one or more penalties could be coming their way. The good news is that if it truly was an accident, and the pilot is honest about what happened, most likely they’ll be assigned remedial knowledge and flight training with an instructor and the event never goes on their record. If the rules are broken on purpose, however, the FAA can temporarily suspend or even permanently revoke a certificate.

Tips For Low-Level Flight

I’ve been fortunate enough to fly dozens of missions across the Midwest that have required a significant amount of low-level flight time. There are several tips I want to share that hopefully will help you stay safe and legal.

1. Plan. Prolific planning is paramount to low-level flight preparations. Know exactly where you are going. Think about who and what else may be nearby and below by thoroughly reviewing sectional charts and NOTAMS. I often use services like Google Earth and the topographic map website sartopo.com to evaluate the terrain and potential safe landing areas. Skyvector.com is a good free source for UAS NOTAMs (aka DROTAMs). Just keep in mind most UAS operators never file a DROTAM. Know and monitor radio frequencies for the airspace you are flying in and don’t be afraid to announce your location and altitude periodically if you are near an airport or busy airspace. Knowing the winds aloft is important for low-level photo missions to help plan the amount of wind correction and bank angle that will be needed. If winds are too strong aloft, the wind correction inputs needed to stay on track may make a good shot from the camera impossible. When flying below 3,000 feet MSL, one of the best sources for winds aloft can be UAS weather apps, but good old-fashioned interpolation works okay too. A GPS can also give you the information needed to determine winds aloft, but flying low at the site is a less-than-ideal time to do so.

2. Overfly the field. Just like we would at a non-towered airport, it is important to overfly your location of interest at a higher altitude. This gives us the opportunity to identify obstacles, people, structures and safe landing areas. Once I feel good about the situation and the plan, we’ll descend to a specific minimum altitude while continuing to scan for unseen hazards. Remember, situational awareness saves lives.

3. Eyes up and moving. Avoid staring down at a target on the ground. We obviously want to enjoy the view – that’s the whole point of the flight, but I constantly remind myself to look up and out. Collision avoidance systems are great, but some other aircraft, UAS, clouds, towers, terrain, and the aforementioned feathered foe might not show up on the screen. If we don’t remain vigilant, they could end up in our windscreen! Looking outside also helps keep the airplane under control and allows us to always keep an eye on an emergency landing site. Determine a minimum maneuvering airspeed (1.404 times VS1) prior to flying and don’t go below it. On the other hand, don’t stare at the instruments either. Once again, be constantly aware of and evaluating your situation.

4. Use the buddy system. For photography missions, I always have somebody else take the photos so I can focus on flying. This makes it especially important to brief the plan of action, including potential hazards and emergency plans with the photographer. It’s great if they are a pilot too, but it’s not necessary. A second set of eyes can be very helpful to see and avoid other traffic. While on the ground, make sure to rehearse where the photographer will sit and shoot, determine if windows/doors will be opened, and how to unplug their mic cable, etc. I also request VFR Flight Following from air traffic control whenever it is available, but at low altitudes, it can be difficult to be picked up on radar. Another good reason to stay higher than the legal minimum if you can.

5. Practice. Those ground reference maneuvers we were forced to master actually do have a purpose. Either go alone or better yet, take a CFI and really strive to perfect those maneuvers. The same goes for maneuvering in slow flight. Make sure to focus on coordination and pay attention to the details of altitude, airspeed, bank angle, pitch angles, etc. The goal is to be precise and accurate while keeping eyes outside almost entirely. I highly recommend learning eights on pylons and commercial standard accelerated stalls, and if you haven’t done them before, just take an instructor and be safe.

Flying low can provide a wonderful and unique vantage point for the world around us. Whether on a low-level mission or just sightseeing, make sure to fly safely and avoid disturbing others as best you can.