by Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman

© Copyright 2022. All rights reserved!

Published in Midwest Flyer Magazine April/May 2022 online issue.

As our avionics continue to improve, many pilots have panel updates scheduled or in pro.ress, and in some cases, these panel updates cost more than the airplane cost when it was originally purchased. Among the updates are Global Position Satellite (GPS) instruments. And as a result, many of us have not flown an Instrument Landing System (ILS) approach in quite some time, because GPS approaches are much easier, as are transitions navigating from GPS en route, to a GPS approach.

I have been doing ILS approaches since I earned my instrument rating almost five decades ago, but they do have several shortcomings. The ground equipment for the ILS is very expensive for the FAA to install and maintain, while the equipment we need in our airplanes to successfully fly an ILS approach can now be purchased for under $1,000. Because the ILS ground equipment is so expensive from the government side, you’ll only find it at major airports and only for one or two runways. The major benefit of an ILS approach over a GPS approach are the lower “minimums.” As far as I know, there are no GPS approaches that have lower minimums than ILS approaches. And “zero-zero” ILS approaches require additional equipment and special pilot training.

To fly an ILS approach, we need an ILS receiver, which is usually part of old VOR and glideslope receivers. A new $70,000.00 panel upgrade will not do a better ILS approach than an old King KX-170 did five decades ago.

As pilots we need to know that there are a few shortcomings to both the ILS approach and GPS approach.

Some 20-plus years ago, I was returning from Florida in my Bonanza and checked the weather for my home airport at the time, Tri-County Regional in Lone Rock, Wisconsin (KLNR) and it was not good. The only approach available at that time was a VOR-A approach with high minimums. So, I decided to divert to Dubuque, Iowa (KDBQ) for the ILS 31, but that airport also had low Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC).

I was being vectored for the approach by Chicago Center as there is no approach control at Dubuque. I checked the Automatic Terminal Information Service (ATIS) and set my altimeter to 29.62 inches, then intercepted the localizer on a vector. The glideslope came alive, and I was on the approach. I always check my altimeter when crossing the final approach fix (FAF) against the published altitude on the approach plate. If this is not one of your procedures when flying an ILS or GPS approach, you could be a candidate for disaster. As I crossed the FAF on the glideslope, I realized I was some 360 feet below the published crossing altitude shown on the approach chart. Not good! Now on the tower frequency with a cleared-to-land clearance, I immediately declared a missed approach.

I then asked the tower for the current altimeter setting and was given 29.26. I must have set the wrong altimeter setting. I was switched back to Chicago Center and was given vectors for another approach. This time, everything checked out crossing the FAF, and I landed without further incident. I taxied to the ramp, turned off my avionics, and shut down the engine, but something bothered me… How could I have made such an important mistake? I decided to turn the radios back on and listen to ATIS again. What I found out was when the controller made the ATIS tape, he transposed the altimeter setting from 29.26 to 29.62. I called the tower and asked them to listen to the ATIS tape, which they did, and the controller acknowledged his error. If I had followed the glideslope correctly to published minimums without seeing anything, I would have been 160 feet lower than I thought I was – lesson learned!

Several years later while training a pilot for an instrument rating doing the same approach at the same airport, a similar situation occurred, but in VFR conditions. Again, I called the tower for an altimeter setting, but this time it matched what was reported on ATIS, so we landed. I figured it was another similar error, but after landing, the altimeter matched the touch down zone elevation. How can this be? So, I called the avionics shop, and they had us bring the airplane to the shop. The glideslope was out of calibration, so it was recalibrated, and everything worked correctly.

Every two years we have a pitot static, altimeter and transponder check done on our airplanes. When flying IFR using VOR for navigation, we as pilots must do a VOR check and log it in the aircraft records, but nothing is said about the localizer or glideslope. I learned that the localizer and VOR use different electronic circuits, and the VOR check means nothing to the localizer.

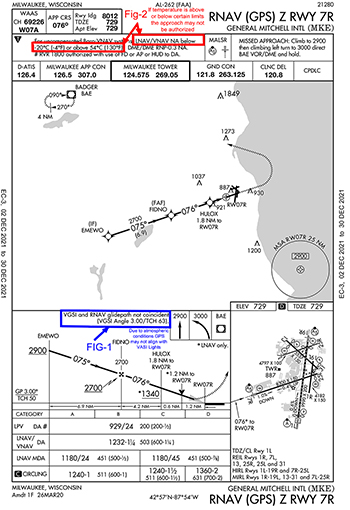

When we look at some of the differences between ILS and RNAV/GPS approaches, we need to be aware of the accuracy of the approach. To the surprise of many of you, the ILS approach, which has been around for about 75 years, is still the winner. We have implemented WAAS which has greatly improved the accuracy of GPS approaches, but it still cannot be as accurate as the ILS approach. This is due to the weather conditions, such as temperature and humidity that affect the radio signals from the GPS satellite. You may see notes on approach plates (FIG 1 & 2) that tell us the VASI may not align with the approach course, or the approach cannot be done if the temperature does not fall between the guidelines needed for obstacle clearance. As depicted, we can see a description of the two services, though both will provide an obstacle clear path to the runway.

A precision approach is an instrument approach based on a navigation system that provides course guidance and glidepath deviation meeting the precision standards of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Annex 10. For example, PAR, ILS and GLS.

An approach with vertical guidance (APV) is an instrument approach based on a navigation system that is not required to meet the precision approach standards of ICAO Annex 10 but provides course and glidepath deviation information. For example, Lateral Navigation and Vertical Navigation (LNAV/VNAV) and Localizer Performance with Vertical Guidance (LPV) are APV approaches.

When we fly the ILS approach today, it is the same as we did it 50 years ago; the difference being how we get established on the approach. We do not need to have a GPS in the airplane to fly an ILS approach, as we did not have GPS when the ILS was first developed. Once established on the inbound course, we fly using the localizer and glideslope, and from a previous article, if we are hand-flying the approach, we learn to dance on the controls to keep those needles centered, especially in turbulent air.

When we are being radar vectored for the approach, GPS is not needed, and it might be better not to use any GPS for reference. I will explain later.

During the radar vector, the controller will specify, or should specify, that this is a “vector for the approach” and will specify the runway on the first vector the controller gives you. The last vector will include an altitude and heading until established, along with the approach, again for pilot verification. This requires a total readback from the pilot… heading until established, altitude and the name of the approach.

When we are going to be flying an ILS approach with radar vectors and without using GPS assist, there are some “gotchas” to remember.

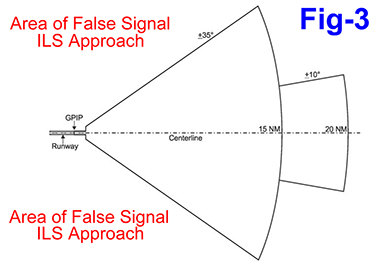

Before GPS, I had a lot of fun with instrument students on this type of approach. There are false signals from the localizer and glideslope that will trick the pilot into thinking they are on the proper signal (FIG 3), so you must fly to the Initial Approach Fix (IAF) and positively identify it, then fly the charted approach as depicted on the approach chart. If you are using GPS assist and flying the full approach with a course reversal, you will not even be aware of these false signals because you are in GPS mode on your navigator.

It is important when either loading the approach or activating the approach the first time, to make sure you load the “ILS frequency” from the standby window to the active window on the navigator.

I recommend that pilots go to settings on their navigator while on the ground and select the option to manually switch from GPS mode to VLOC mode for ILS approaches. The GPS does a much better job of getting the airplane correctly established on the inbound course, as the “auto switch” occurs once inbound on the procedure turn. Autopilots flying roll steering (GPSS) do a much better job getting established on the inbound course than trying to capture a localizer signal in VLOC mode.

The last configuration on flying an ILS approach, which I mentioned earlier in this article, is using GPS assist when getting radar vectors and why this could fool you if you are unaware of how it works.

You have been told by air traffic control (ATC) that you are getting radar vectors for the ILS approach, so you load the approach, put the ILS frequency in the active window and then select “vectors to final” on your GPS navigator. ATC starts vectoring you and suddenly you notice that your navigator shows “suspend,” kind of like when in a holding pattern. This does not always happen as it depends on where you are in relation to the inbound approach course. As you follow the vectors from ATC, you notice the navigator is still in suspend and you know that pushing the OBS button takes you out of suspend. It is tempting to push that button, but don’t do it, as it will come out of suspend automatically at the proper time. Pushing the OBS button will cause the box to sequence to the next waypoint and this would be bad.

Remember, when using the GPS navigator on vectors to final, there will be no magenta line to follow until on the inbound approach course.

In conclusion, go ahead and fly the ILS approach when offered to help you stay current. Better yet, practice with a safety pilot or instructor before you tackle it in IMC. It is not difficult to do, though there are a few more steps involved than sitting back and just watching the airplane fly the GPS approach with no pilot input.

Stay safe and train often with an experienced instructor.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman is a Certified Instrument Flight Instructor (CFII) and the program manager of flight operations with the “Bonanza/Baron Pilot Training” organization. He conducts pilot clinics and specialized instruction throughout the U.S. in many makes and models of aircraft, which are equipped with a variety of avionics. Mick is based in Richland Center (93C) and Eagle River, Wisconsin (KEGV). He was named “FAA’s Safety Team Representative of the Year” for Wisconsin in 2008. Readers are encouraged to email questions to captmick@me.com or call 817-988-0174.

DISCLAIMER: The information contained in this column is the expressed opinion of the author only, and readers are advised to seek the advice of their personal flight instructor and others, and refer to the Federal Aviation Regulations, FAA Aeronautical Information Manual, and instructional materials before attempting any procedures discussed herein.