by Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman

Published in Midwest Flyer – June/July 2020 issue

As I am writing this article, there is doom and gloom as the world seems to be shut down for the Coronavirus Pandemic. I am anxious to go flying, but finances are uncertain, so I go to the airport, pull the airplane out of the hangar, and sit inside making airplane noises and try to learn more about my new “to me” avionics and interfaces. I find it interesting to learn about how all of these boxes play together. I have a simulator on my computer for the Garmin 480 that I just installed, and it is interesting to see information programmed on the navigator populate the Garmin area 660 and iPad.

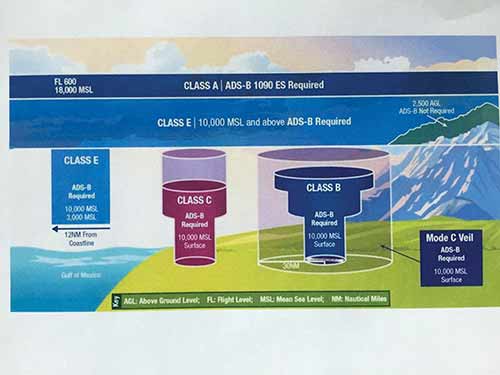

I recently had phone conversations with pilots who are still trying to decide if they want to spend the money on an ADS-B out box, and if they chose not to, where could they go or not go in the U.S. airspace system. In the state of Wisconsin, we only have three Class C airports and no Class B airports. The general rule on ADS-B out requires that it is necessary for any airspace that previously required a Mode C transponder to follow the same list as shown below.

I have been questioned on flying under the shelf of a Class B or C airport to land at a satellite airport, and my interpretation is NO for Class B, but YES for Class C based on the diagram below. I would be interested in comments from our readers on that one.

• Class A, B, and C airspace;

• Class E airspace at or above 10,000 feet MSL, excluding airspace at and below 2,500 feet AGL;

• Within 30 nautical miles of a Class B primary airport (the Mode C veil);

• Above the ceiling and within the lateral boundaries of Class B or Class C airspace, up to 10,000 feet. (Note that ADS-B is not required below a Class B or Class C airspace shelf, if it is outside of a Mode C veil);

• Class E airspace over the Gulf of Mexico, at and above 3,000 feet MSL, within 12 nm of the U.S. coast.

I was also curious about the rule that applies to aircraft not originally certified with an electrical system, such as my J-3 Cub on floats or wheels.

Some years ago, I flew underneath an overlying Class B airspace and through Class D airspace to land on a lake. I had used a handheld radio to contact the tower of the Class D airport. The controller asked for a transponder squawk, and I replied, “negative transponder.”

Prior to leaving the Class D airspace, I was given a phone number to call after landing. The phone call was made and after clarifying the rule allowing this operation, no further action was needed.

My memory recalls another requirement that a landing must be made, and that the aircraft must traverse via the shortest distance both into and out of this airspace en route to the landing site. I was unable to find this requirement during my search.

The regulation 14 CFR 91.225(e) allows aircraft not certificated with an electrical system, including balloons and gliders and many light aircraft built in the 1940s not equipped with ADS-B Out, to operate within 30 nautical miles of a Class B primary airport – basically, within its Mode C veil – while remaining outside of any Class B or Class C airspace. These aircraft can operate as high as 17,999 feet MSL, except above Class B or Class C airspace. They also can operate beneath Class B and Class C airspace. Operationally, the ADS-B Out rules mirror the transponder equipage requirements in 14 CFR 91.215. Equipping with a transponder and ADS-B out allows for operations above Class B and C airspace.

I have heard the comment from pilots that a cross-country trip without ADS-B would add a lot of miles and time onto their flight. I used ForeFlight on my iPad to plot a trip from my home airport in Richland Center, Wisconsin (93C) to Lakeland Linder International Airport in Lakeland, Florida (KLAL). The direct trip was 1,001 nm and after editing the flight to avoid airspace requiring ADS-B out, the trip was 1,007 nm. The big issue was on the end of the trip as KLAL was underlining the 30 nm veil of Tampa’s Class B airspace, but only by about 2 miles. For those pilots going to Sun ‘n Fun next year, I would imagine there would be a waiver. That’s worth checking into and verifying if your aircraft is not ADS-B out equipped.

Handling Distractions In The Cockpit

An issue that has plagued people with such things as texting while driving, and pilots programing a navigator while taxiing, is how to avoid such distractions. Many of you have seen the classic video on YouTube and other video streaming sites of the Cessna Cutlass on final approach with the rear seat passenger taping the landing (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-K4QHpVXtxI).

There is a distinct horn sound blowing in the background as the pilot and front passenger are talking. The horn that was blowing happened to be the gear horn, and as the plane made a perfect landing, there was a scraping sound as the airplane slid to a stop on its belly. There were no injuries in this case, except to the pilot’s pride, but this is not always the case.

I spend a lot of time flying seaplanes, and I always have a fear of flying an amphibian because my seaplane is on straight floats with no gear to worry about. Should you land an amphibian in the water with the gear down, your odds are not so good. Sixty percent (60%) of those landings have a fatality, as the seaplane will flip over, and the pilot or passenger cannot get out and thus drowns. Several companies have made safety devices with an audible warning to alert the pilot, “Gear is UP for water landing” or “Gear is DOWN for runway landing.” The issue is like the gear horn on the Cessna Cutlass if the pilot is distracted.

The airlines have a sterile cockpit policy below 10,000 feet, meaning no chit chat other than discussing the flight. In instrument training, we find similar situations as I watch pilots fly through the localizer course or miss the glideslope intercept while hand flying, or forget to properly activate the approach on the navigator or autopilot. We have so many cool new avionics boxes, which keep tempting the pilot to get more flight information. Distractions don’t necessarily need to be a person in the cockpit or a call from air traffic control.

When I instruct instrument pilots for an instrument rating, I try to show them how simple an approach can be and what information is important once inside the final approach fix (FAF). Once inside the FAF, I tell my students to “give me your approach chart or iPad and concentrate on flying the airplane,” should I find them distracted by the approach chart or multi-functional display (MFD).

Three items of memorization are all you need from the FAF to landing or the missed approach point (MAP):

1. How low can I go (altimeter)?

2. What is my MAP (altitude, fix or time)?

3. What is the initial part of the missed approach, should I need to go missed (climb straight ahead or with a right or left turn)?

In cases where we are flying a precision approach, items 1 and 2 are the same because the MAP is the same and should begin when reaching decision height (DH) or decision altitude (DA).

When we get distracted, we forget to fly the airplane when hand-flying. When flying on autopilot, the pilot should monitor these instruments as if he were hand-flying the airplane, because if the auto pilot fails, he will be hand-flying the airplane.

If you have a flight director and flying with a safety pilot, try covering up or dimming down everything except the flight director and hand-fly an approach “by the numbers” once inside the FAF. The only other instrument needed is the altimeter for your DA or DH.

I could fill this entire issue of Midwest Flyer Magazine or write an entire book on distractions in the cockpit, and the accidents they have caused.

For instance, there is a case of an airliner with two pilots flying into the ground or controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) due to distractions. Regrettably, all died.

In another situation, ATC requested a student I was training to execute a 360 for spacing on his final approach to land, which distracted him from his normal routine. Had I not taken the controls 50 feet above the runway, he would have done a classic gear up landing.

And pilots programing their GPS while taxiing have run off the taxiway and damaged their airplanes.

Stay focused, avoid distractions and fly safe!

EDITOR’S NOTE: Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman is a Certified Instrument Flight Instructor (CFII) and the program manager of flight operations with the “Bonanza/Baron Pilot Training” organization. Kaufman conducts pilot clinics and specialized instruction throughout the U.S. in a variety of aircraft, which are equipped with a variety of avionics, although he is based in Lone Rock (KLNR) and Eagle River (KEGV), Wisconsin. Kaufman was named “FAA’s Safety Team Representative of the Year” for Wisconsin in 2008. Email questions to captmick@me.com or call 817-988-0174.

DISCLAIMER: The information contained in this column is the expressed opinion of the author only, and readers are advised to seek the advice of their personal flight instructor and others, and refer to the Federal Aviation Regulations, FAA Aeronautical Information Manual and instructional materials before attempting any procedures discussed herein.