by Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman

© 2021 October. All rights reserved!

Published in Midwest Flyer Magazine Online October/November 2021 Issue

I have been quite active during the summer months doing accelerated instrument training and reviewing and updating my PowerPoint presentations for my BPT Seminars. I was amazed at the changes that have occurred in how we fly on instruments, which has occurred because of the advent of the GPS, and the sophisticated navigators we now have. In some cases, the way we get established and fly approaches has gotten easier, but some have gotten harder.

We need to know the proper way to set up an approach in a navigator, which menu to use and which button/buttons to press. If we have touch screen technology, turbulence can require us to make several attempts to get the right approach and the right waypoints loaded in the box.

Several weeks ago, while attempting to program my GPS navigator during a flight in turbulence, I came close to becoming an example of CFIT (controlled flight into terrain). I was flying on autopilot and had it programmed for a descent while attempting to make a route change. It took me three or four attempts to spell out the identifier of the waypoint, and I missed my level-off altitude by a large margin. This was definitely a pilot error, and human factors were major contributors as well.

What could I have done differently? I should have kept a scan going on my instruments and pushed altitude hold on the autopilot when reaching my level-off altitude. Some may say, why didn’t you use altitude preselect? I did not have one, and even if I did, I would not use it as I have seen too many glitches – mostly in incorrect programming by the pilot. The human factor here was that I was getting extremely frustrated for not being able to get the waypoint in the navigator; my frustration overcame good judgment. I prefer hard keys and knobs to twist when programming a route change on a navigator.

We have seen tremendous breakthroughs in voice technology in recent years. I have become a geek to my Amazon Alexa device: “Alexa, open airport weather… Get Kilo, Echo, Golf, Victor” (KEGV, Eagle River Union Airport, Eagle River, Wisconsin). I am hoping the next generation of aviation navigators will encompass voice recognition for programming. Who will be the first to have this feature? “Dynon, load the GPS 36 approach for Kilo, Oscar, Sierra, Hotel?” (KOSH, Wittman Regional Airport, Oshkosh, Wisconsin).

When we fly an approach today, most of us will use some feature of a GPS navigator, even though it may not be a GPS approach.

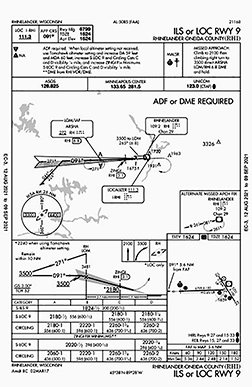

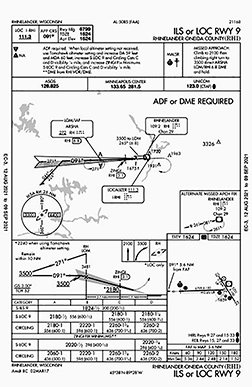

FIG 1

For example, if I were doing the ILS 09 approach to Rhinelander-Oneida County Airport (KRHI), I would use the GPS navigator to call the shots until I was established inbound 2 miles outside the final approach fix (FAF). I thought it would be fun to do that approach, as I haven’t done it in recent years (Fig 1). For the sake of nostalgia in this article, I will portray this scenario as it would have been done 30 years ago. A note of interest: this approach has not changed much over that period time.

Some 30 miles south of the Rhinelander airport, I received a call from Minneapolis Center: “Bonanza N9638Y, current Rhinelander weather is 600 overcast, visibility 2 miles, light rain, wind calm, altimeter 29.76. What approach would you like?”

I replied: “I would like the ILS 09 approach with the Rhinelander VOR transition.”

Minneapolis Center: “You can expect that. Proceed direct to the Rhinelander VOR.”

I have a King KX175 nav/com, an ADF and a marker beacon receiver in my airplane. I already have the Rhinelander VOR frequency of 109.2 MHz in the NAV side of my KX175, the VOR indicator is set to 350 degrees, and the CDI is centered. I am now 10 miles from the VOR at 5,000 feet.

Minneapolis Center: “Bonanza N9638Y, you are 10 miles from the Rhinelander VOR. Maintain 4,000 until established on a segment of the approach. You are cleared for the ILS 09 approach to the Rhinelander airport. Cancel IFR on the ground through flight service. Switch to advisory frequency approved.”

I replied: “4,000 until established. Cleared for the ILS 09 to Rhinelander.” Note, ATC needs more than a “ROGER” on an approach clearance. Your readback should include altitude and the name of the approach.

I begin my descent to 4,000 and continue to track the VOR to the airport. Note the small arrow on the approach chart to the left of the VOR symbol. This is the transition arrow showing the radial of 265 degrees and 6.8 nm, taking us to the initial approach fix (IAF) of “ARSHA,” also the published altitude of 3500 feet as a published segment. Arriving over the VOR, I use the “Five T’s:”

Turn

Time

Twist/Track

Throttle

Talk

Turning the aircraft to a heading of 265 degrees, nothing to time, twist my VOR to 265 degrees and (turn) slightly to intercept the 265-degree radial to my outbound course (track), reduce power (throttle) to descend to the 3500-foot published altitude, and announce my position (talk) on the airport advisory frequency. Looking at the approach chart, I see there is an ADF/LOM (Locator Outer Marker) at the ARSHA fix, and I have both and my ADF is tuned to 272 kHz. I notice my ADF is pointing to ARSHA, and I have identified the Morse Code on the ADF, as I had done previously with the Rhinelander VOR.

Upon crossing ARSHA, which is shown by the marker beacon light, the marker sound and the ADF pointer reversing, I again use the “Five T’s” and make a slight turn to 271 degrees, followed by a twist, but this time the twist is changing the radio frequency to the localizer frequency of 111.3 MHz, followed by a start of the timer to track outbound for approximately 2 minutes. Note, the switch to the localizer frequency should be done here, and we must remember tracking outbound on a localizer front course has reverse needle sensing (no HSI) on the CDI, and we need to identify the Morse Code for the localizer.

After approximately 2 minutes, our approach plate tells us to begin the procedure turn to the left of approximately 45 degrees or a 226-degree heading. Again, the “Five T’s” come into play with timing of about a minute and spinning the VOR or HSI needle to the inbound course of 91 degrees. After the timer expires for a minute, we do a 180-degree turn to 46 degrees, double check with our “Five T’s” to see what we forgot and watch for the localizer needle to come alive. At this point, we turn in to capture the CDI and we are inbound to ARSHA, waiting for the glideslope (GS) needle, and our approach now becomes identical to what we would have seen had we been flying using a GPS navigator.

In review, what we did and how we did it more than a decade ago, was not that hard. We did not need to select an approach on our navigator or choose our initial approach fix (IAF) or transition and go through a bunch of button-pushing in turbulence. On the flip side, the autopilot could have flown the entire approach with almost no pilot input, except power, once we had it loaded, had we used a GPS navigator.

On your next instrument training flight or proficiency check, challenge yourself and go back 30 years and see if you can still remember how to fly an ILS approach this way.

Until the next issue of Midwest Flyer Magazine, always fly safe!

EDITOR’S NOTE: Michael J. “Mick” Kaufman is a Certified Instrument Flight Instructor (CFII) and the program manager of flight operations with the “Bonanza/Baron Pilot Training” organization. He conducts pilot clinics and specialized instruction throughout the U.S. in many makes and models of aircraft, which are equipped with a variety of avionics. Mick is based in Richland Center (93C) and Eagle River, Wisconsin (KEGV). He was named “FAA’s Safety Team Representative of the Year” for Wisconsin in 2008. Readers are encouraged to email questions to captmick@me.com or call 817-988-0174.

DISCLAIMER: The information contained in this column is the expressed opinion of the author only, and readers are advised to seek the advice of their personal flight instructor and others, and refer to the Federal Aviation Regulations, FAA Aeronautical Information Manual and instructional materials before attempting any procedures discussed herein.