by Dean Zakos

© Dean Zakos 2021. All Rights Reserved!

Published in Midwest Flyer Magazine December 2022/January 2023 Digital Issue

I always wanted to fly.

I liked the satisfaction of rising up and meeting challenges. I thrived on being presented with, or happily sought out, opportunities to test myself. I wanted to see how I performed – in school, in sports, or against other men in airplanes or helicopters. Did I measure up? I usually satisfied myself that I did.

Well, I am being challenged tonight.

I am flying alone in a Beechcraft B80 Queen Air. The airplane, a twin-engine corporate and light transport aircraft, is owned by Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, my employer. It requires only a single pilot and can be configured for carrying up to 11 passengers or cargo. Max speed is 208 kts and normal cruise is about 180 – 190 kts. Max payload is 3,000 lbs., and GTOW is a little over 8,000 lbs.

The B80 is powered by two Lycoming IGSO-540-A1D piston engines rated at 380 hp each. The wingspan is 50 feet, 3 inches, and its length is 35 feet, 6 inches. I found it to have good flight characteristics and a pleasure to fly.

In 1972, Lockheed was bidding on the U.S. Army’s Cobra helicopter follow-on program with the AH-56A Cheyenne Advanced Attack compound helicopter. The Cheyenne had a four-blade main rotor, a four-blade tail rotor, an aft mounted three-blade pusher propeller, and low mounted aerodynamic wings, with hard points for launching anti-tank missiles and rockets. Powered by a single 4,275 shp GE-T64-716 turbo shaft engine, it flew at over 200 kts in some operational tests. Designed with a two-seat tandem cockpit, a gunner sat in the forward seat, which rotated 100 degrees to either side of centerline. This flexibility enabled the gunner to locate a target and remain locked-on to it regardless of the pilot’s flight maneuvers. The pilot occupied an elevated rear seat that offered excellent visibility to the front and sides. The prototype helicopter handled well and was fun to fly.

Lockheed’s program was operating from a test area called the Castle Dome Development site at the Army’s huge Yuma Proving Grounds in Arizona. We had a good facility about 40 miles west of Yuma, with a single, non-lighted runway.

A number of Lockheed employees decided to move temporarily to Yuma for the duration of the program. Others stayed in motels in Yuma during the week, opting to be shuttled from Burbank on Monday mornings and back to Burbank on Friday afternoons. These charter flights operated out of Laguna Army Airfield (KLGF), not far from Castle Dome. My wife and I decided to keep our family in the Los Angeles area, and so I became one of the weekly commuters.

Because of my status as a test pilot on the project, I was offered an occasional respite from being a passenger on the weekly commuter flights. Lockheed had its own “personal transport” available for the project, the Beechcraft I am flying. Often, to maintain schedules, ferry personnel, or quickly confirm test results, I was asked, as needed, to fly parts, passengers, or test data to and from Yuma. I would usually depart Laguna on short notice and fly direct to Van Nuys (KVNY), which was located close to Lockheed’s facility. Earlier today, I was asked to make a “data run,” transporting test data containing many lines of specialized code. A Lockheed tech employee would meet me at the Van Nuys airport and then drive the data to Lockheed’s offices where people and computers “crunched the numbers” and interpreted the raw data. Reports generated from the data would then be loaded back on the Queen Air for the return flight to Yuma at the end of the same day and be available for review the next morning when the morning crew in Yuma came in for work.

As I rotated the Queen Air and started my climb out of Yuma this morning, I took a moment to admire the painted colors of the desert slipping by below me. The vast ranges of sand and sagebrush, with layered purple mesas rising in the distance were stark, but beautiful. The Queen Air entered the overcast at just about 1,000 feet above the ground. The balance of the trip from Yuma to Van Nuys was solid IFR, with no precipitation, but with some snow showers possible in later forecasts for the return flight. Upon landing in Van Nuys, I was informed the data would take several hours longer than the normal three-hour turnaround time to process, so the results would not be available for me to transport back to Yuma until that evening. I was actually pleased with the news, and I quickly grabbed a company car and headed home to spend a little time with my wife and three girls.

After dinner that night, with goodnight hugs and kisses all around, I headed back to the airport, as I was advised the data had been processed and the stacks of completed reports were being loaded onto the plane. That scenario was pretty much how most data runs went. The return flight to Yuma ordinarily averaged about an hour and a half. This night, in early December 1972, was going to prove to be different.

Winter weather conditions were moving into the area along my planned route. Snow was no longer forecast for my return to Yuma, but lower freezing levels and turbulence were. The Queen Air was equipped for winter operations, with wing de-icing boots, fuselage-mounted lights to confirm wing ice status, heated windshield de-ice, and prop de-ice.

My IFR flight plan, with a 2100 (local) departure, was to climb to and maintain 6,000, Van Nuys direct Ontario. Then, direct Julian, direct Coyote Wells, Victor 137 to El Centro, then direct Yuma/Laguna. Flying the leg to Ontario, I encountered no significant weather, but there was some occasional moderate turbulence. I turned all de-ice equipment and pitot heat on as soon as I was in the clouds, except prop de-ice. On the leg to Julian, I experienced more turbulence and windshield ice was starting to form in corners and on protruding surfaces. I called LA Center and reported the ice, requesting another route. Center suggested a turn to 325 degrees, back toward Ontario, adding that two airliners had just departed Ontario and were not picking up ice. I made the turn and remained at 6,000 feet.

I was not concerned – yet.

My thoughts momentarily traveled back to earlier days and how I found myself sitting in the left seat of the Queen Air. Knowing of my interest in aviation as a boy, my father arranged for my first airplane ride. He had a friend who was the chief pilot for a large manufacturing company. The company owned a de Havilland DH.104 Dove, a twin-engine, polished aluminum beauty, which was used to transport businessmen and customers. From that flight, I knew I wanted a career in aviation.

I attended the University of Wisconsin and graduated in 1956. I met my wife there. While in the business school, I was also in an ROTC program. Upon graduation, I joined the Navy (a childhood dream of mine). At Pensacola, I was introduced to military flying, first in a Beech T-34 Mentor, then a North American T-28C Trojan. After winning my gold wings, I was assigned to a squadron flying Douglas A-4 Skyhawk attack jets. I flew two tours in Skyhawks from carrier decks (the USS Ranger CVA-61 and the USS Enterprise CVA-65) off the coast of North Vietnam until, on one mission, in a rapid descent while suffering with a head cold, one of my eardrums burst. I could no longer fly jets, so I asked for helicopters. I piloted a Sikorsky SH-3A/D Sea King on an additional deployment in Vietnam.

After my active-duty service, I applied to the airlines and to some defense contractors. United Airlines and Lockheed offered me jobs. Both letters arrived in my mailbox the same day. My background was more a natural fit with Lockheed, as I was a “rotor head,” had acquired experience in the Navy as a “systems guy,” and had earned an MBA degree during one of my rotations to shore duty.

I did encounter some ice in jets in the Navy, be we often flew so high and fast that it was never really an issue. At 6,000 feet in the Queen Air, doing about 180 kts, picking up ice was a very real possibility. Ice continued to accrete on the windshield, even with the windshield de-ice on. Fuselage lights showed no wing ice yet. Solid IMC. Prop de-ice is now on. I was relatively confident of the Queen Air’s de-ice capabilities should things get worse.

I am hand-flying – no autopilot – and doing careful crosschecks. My eyes move across the panel, from pitch to bank to power instruments. From attitude to airspeed, then vertical speed, then attitude again. Next, heading, compass, and turn and bank – all okay. Manifold pressures and prop RPMs steady. Suddenly, severe turbulence angrily invades my solitude and destroys my orderly instrument scan. I had taken the precaution of making sure my seatbelt was secure, but the convulsive forces on the control surfaces catch me off guard. Coming rapidly and unpredictably – left, right, up, down – I could not guess from which direction the next impact would hit me or anticipate how I could counter it. The Queen Air was being thrown violently around the sky. The instrument dials blur and are difficult to read. The aircraft’s angle of attack increases and decreases wildly in just seconds. The yoke is trying to bang against its stops.

Forget about holding altitude or heading. I try to concentrate on keeping the wings level. I have both hands tightly gripping the yoke as it forcibly bucks and gyrates in front of my chest. Instead of me pushing on the rudder pedals, the pedals punch erratically against my feet. I am fighting for control. I do not know if I am in command, or the turbulence is. I think about reducing airspeed to Va so the airplane will somehow continue to hold together in this fearsome pounding.

I glance hastily out my side window. Through the dark gray mist streaming by the fuselage lights, I see it. Ice. Ice everywhere! I was distracted by the turbulence. The rocking and rolling, so hellacious a moment ago, has abated somewhat. The airplane is semi-controllable, giving me a chance to concentrate. I check to make sure all de-ice equipment is on. It is. I cycle the wing de-ice boots. Nothing happens. I do not touch the throttles. The airspeed indicator confirms that the weight and aerodynamic drag of the accumulated ice is already slowing me down. The windshield is frozen over. I struggle to believe what I am seeing. The de-ice systems are failing me.

I sometimes wondered about a moment like this in a lifetime of flying. Will I think of my family? I could not bear to lose them. Will I panic or will I remain in control of my emotions? I have managed fears in the past. Sitting here now, I can feel my body’s natural response. Adrenaline is coursing through me; blood pressure up; face flushed; heart racing. Short, quick breaths. But I can still think clearly. I make up my mind. Taking some intentionally slow, deep breaths, I banish the desperate and unwelcomed thoughts as quickly as they come. I will fly the airplane. I can get out of this.

Suddenly, a sharp, metallic banging on either side of the B80’s nose in front of me. What is that? It sounds a little like the sound a seatbelt buckle makes if inadvertently locked outside the door of a small plane, the buckle free to strike crazily against the door in the slipstream. After a moment, I know. It is the prop de-ice slinging chunks of ice off the blades and against the thin aluminum skin of the airplane. The staccato sound is not rhythmic; it is loud, seemingly random, and a little asymmetric, with the left side taking more of a beating than the right side. It starts, stops, and then starts again.

The altimeter is slowly, steadily, unwinding. I am sinking out of my current altitude. Airspeed degrading. 130 kts now. Book stall speed is 80. I push throttles full forward to takeoff power, mixtures to full rich, and props full forward. The fuselage lights are now frozen over so I can no longer see the amount of ice building on the wing leading edges and across the upper surfaces. My feet dance on the rudder pedals, trying to keep the ball centered. Wrestling with the yoke to maintain wings level. Even with full power, I am still descending. Am I going to ride this airplane into the ground?

Jagged bolts of lightning now tear the black fabric of the night and light up the amorphous clouds engulfing me. Thunder crashes and reverberates in my ears. Turbulence continues to bat me around relentlessly. Never before have I so much wished to be somewhere – anywhere – else. I continue to battle the controls, but now I think I am losing.

I need to turn a few degrees to the left to try to get back on course, but the airplane seems to have a mind of its own. It wants to drift right instead. Sluggish and heavy on the controls. It feels as if I am flying sideways. Airspeed now 110 kts. With the load of ice, I am carrying, at what speed does the airplane stop flying? I remain alert for the stall warning horn. At any moment, the alarm could go on – and stay on. I wipe perspiration from my forehead with my shirtsleeve. My mind reels. What happens if the Queen Air stalls and falls out of the sky? At my current rate of descent, I will not have much time or altitude above the terrain to attempt a recovery.

A few moments later, I hear a short, loud boom. The aircraft is shaking noticeably. I think, “This is it!” Almost fearing to look, I turn my head to the side windows. The ice, inches thick in places, is slipping off the wings and engine nacelles in large sheets and in little pieces, disappearing into the black void behind me. Chunks of windshield ice are melting away. Then, it is almost all gone. Having descended below the overcast, the air is now clear and smooth. Airspeed and rate of climb increasing. The altimeter reads less than 3,000 feet. I am in control of the airplane again.

The lights of the city of Banning are visible to my left, Palm Springs to my right. I have not called a Mayday because I was too busy dealing with the emergency. I radio LA Center and, in as calm and as steady a voice as I can manage, I cancel my IFR flight plan and provide a PIREP on my just concluded ride in the turbulence and ice. I advise them my intention is now to proceed VFR direct Laguna.

Visibility under the overcast is excellent. I can see the Salton Sea, with hundreds of lights from residential neighborhoods, observable in the distance. In a few more minutes, El Centro and Yuma appear over the nose of the B80.

I make straight in for Runway 06, and land at KLGF. Seeing the runway lights on short final growing larger in the windshield in front of me is a welcomed sight. Earlier, during the worst of it, I was not certain I would ever land this airplane under control again. Boxes of processed data reports, securely tied down in the cabin behind me, are turned over to a waiting Lockheed employee. The employee makes no comment to me, although I must look ashen from my bout with the elements. The Queen Air, glistening in the hangar’s light and still dripping in places from the melted ice, is put away for the night, but not before I perform a walkaround. I notice a significant number of small, irregular-shaped dents on the left side of the fuselage, just about in line with the arc of the prop blades. Physical confirmation of my ordeal. I will tell them about the damage in the morning.

Now more relaxed, but physically spent, blood pressure and heart rate close to normal again, I am introspective on my drive to the motel. Two big questions: “Why did the de-ice equipment on the Queen Air, about as sophisticated and effective as any available, not perform better on this stormy night?” and “Why did I survive to tell the story?” In response to the former question, I think the technical answer is that the ice I encountered simply overwhelmed the de-ice systems. The rate of accumulation of ice exceeded the ability to shed it. As to the latter question, I cannot provide an answer. I have thought about it often. I wish I could.

Given the known ice certification of the Queen Air and the forecast information I reviewed at the time of my departure from Van Nuys, the intended flight presented a reasonable and manageable level of risk. What I could not know was, on this gloomy and random night, a demon lurked in the clouds. A cold, merciless demon, whose unwelcomed embrace has wrecked airplanes and claimed the lives of countless pilots and passengers in the past, and who will do so again in the future. Tonight, the demon stalked me.

I enjoyed a wonderful Christmas with my family in 1972. I had much to be thankful for.

In the end, the Cheyenne Attack helicopter was not chosen for further development and production. The Army opted instead for the Hughes AH-64 Apache Attack helicopter. I still believe the Cheyenne performed as well or better, and was as capable, as the Apache. But, after all, I am a Lockheed guy.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dean Zakos (Private Pilot ASEL, Instrument) of Madison, Wisconsin, is the author of “Laughing with the Wind, Practical Advice and Personal Stories from a General Aviation Pilot.” Mr. Zakos has also written numerous short stories and flying articles for Midwest Flyer Magazine and other aviation publications.

DISCLAIMER: This article involves creative writing, and therefore the information presented may contain fictional information, and should not be used for flight, or misconstrued as instructional material. Readers are urged to consult with their flight instructor about anything discussed herein.

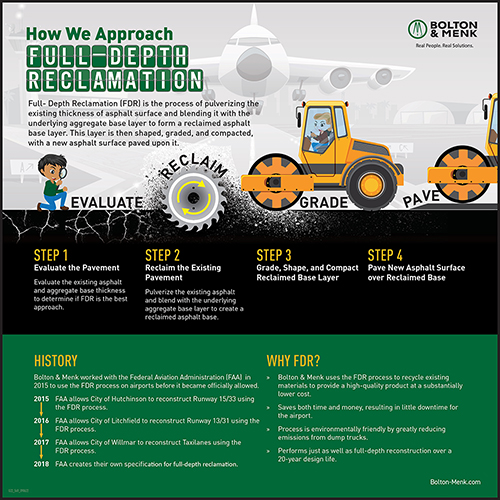

Kelly Halada – Assistant Aeronautical Environmental Coordinator

Kelly Halada – Assistant Aeronautical Environmental Coordinator Jesse Friend – DBE/Labor Compliance Specialist

Jesse Friend – DBE/Labor Compliance Specialist Tyler Leslie – Airport Engineering Specialist

Tyler Leslie – Airport Engineering Specialist Colin Davidson – Airport Development Engineer

Colin Davidson – Airport Development Engineer Samuel Lee – Airport Development Engineer

Samuel Lee – Airport Development Engineer